Imagine the following:

You just came out of a movie sequel that you have been waiting for for years. The thirst for knowledge the movie franchise instilled in you in its starting years has finally been quenched (for now). As you picture yourself being the wizard/superhero/gladiator in the movie, you reflect on how amazing the movie was, and how you can’t wait to discuss it with the world.

*friend enters from stage-left*

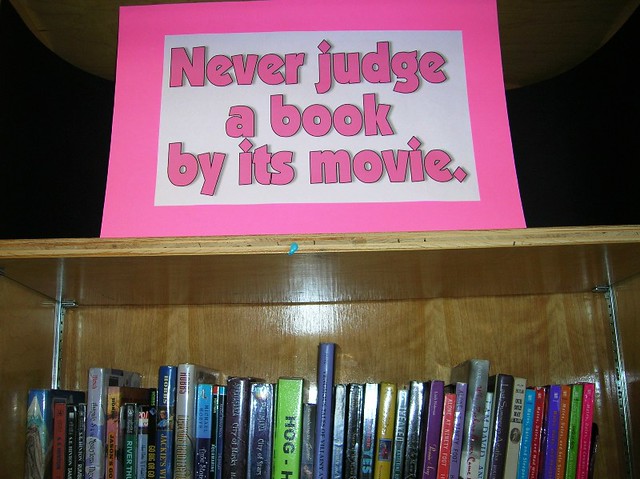

You start talking about the movie. As you put all your heart and soul into describing the wonders and intricacies this great movie has provided you with, your friends replies with the dreadfulness that is the statement: ‘Hmm yeah, but the books are better”.

Depending on if you have read the books in question or not, you might approve or disprove off the statement, but often we find an inherent snobbish tone along this statement, and the question arises: what about the books make it better?

The freedom of imagination?

The amount of words?

The fresh smell of a dead tree in your hands?

In order to find some sort of believable counter-answer to this centuries-old statement, this blogpost will aim at evaluating information outlets and their qualitative value in Popular culture, mainly Written information (Books, Comics) and Visual Information (Videos, Movies).

So what came first: the movie or the book?

In most cases, the visual representation of information requires some sort of written information to exist. A frequent approach of film producers is to choose a book(s) that has gained popularity in the world, and that has the potential to be successfully re-made into a movie. Books can be comprised of 100 pages, 400 pages or well beyond 1000 pages, but the time it takes to finish one depends on a person’s agency to finish it. The fact that we can start/stop reading a book whenever we please, makes books a fixated source of information that is only put in motion when we read it, and our brain processes it into interpretations/imageries in our mind. This gives writers a vast amount of freedom on which imageries to call up in their works, and how they want to guide the reader to get to it.

An example of this would be:

At dawn, the banana was on the floor.

vs.

As the sun found its way into the ocean, a ray of light exposes a tropical fruit on the pier’s cold pavement. Alas, t’was a banana.

This does not mean, however, that the reader is inherently forced to imagine what the author wants us to imagine. We all have different associations with different words. One person’s cognitive interpretation of the words ‘dragon’, ‘spaceship’ or ‘chair’ will thus inherently vary to some degree from another. The reader thus has the freedom to interpret a book in their own conception, guided by the words of the author and the associations inherent in those words.

In movies, however, these freedoms are not available. Everything is as it seems, and the brain takes the images as they are presented. Rather than ‘imagining’, ‘understanding’ becomes the main aim of visual information.

If I show you a picture of a big, green apple, that’s exactly what you’re gonna see. There is no way for words to distort the picture in your head, because it is exactly the picture you’re seeing. In this sense, your freedom of interpretation in movies is reduced to the image the film wants you to see. These are inherently less freedoms than a book would give you, but does that make it worse in comparison? Movies/videos are often bound to “realistic time limits”, that books don’t have. No one will watch a 40 hour movie, but people will spend 40 hours reading. The amount of information we receive from a 600 pages book, cannot be one-to-one replicated in a movie, and should thus be compared with care.

Comparisons should be made between what can be compared and what should be compared. Two red apples are comparable. They are both fruits, they are both red. One is bigger than the other, and one is ripper than the other. Why does this comparison work? Because it starts off from fair premises that judge the compared in their own terms. They are both apples, and are ‘free’ to do what apples do, and be judged on how they are doing as apples. However, once you bring in an orange, you can only compare them to a certain degree.

A healthy example of when to compare.

The apple is a fruit like the orange.

Comparison: Works.

Standards of comparison: Fair, they’re both fruits, and are compared based on that standard.

The apple is better than the orange, because the apple is sweeter.

Comparison: Works.

Standards of comparison: Unfair, because the premise of comparison favors the apple, as it has less citric acid to distract from its sweetness.

The same holds true for book/movie comparisons. A book might have more freedoms for the reader’s interpretation of it, but it is only better than a movie if ‘Freedom of Self-Interpretation’ is the criterion of comparison. This comparison holds, but it is inherently unfair to movies and other visual forms of information. Of course many will argue, that because a book has more information it is thus better, but such a comparison is simple-minded and doesn’t take the freedom of artistic expression of individuals into account, which protects movies to be as an individual’s/collective’s interpretation of written information.

So what should I tell them art snobs?

In conclusion, the main idea to be filtered out of this analysis would be that information is free to be expressed in all ethical ways available, and that comparisons can only be seen as valuable if the fair conditions of judgement are met. And I’m not saying one cannot compare, I would just advise that what one is comparing can even reasonably be compared, cause if not they’re probably just being a snob.

And the same holds for people. Don’t compare yourselves to others, only yourself. Example below.

First off, I love the banana allegory; I just laughed out loud far too loudly for 9AM in Wijnhaven,

I have to admit… I’ve been _that_ friend on multiple occasions, due to my own biases from having read the book first and then finding the movie not quite up to par. A lot of what you’ve written holds true, especially the bit about the visual adaptations having specific time limits – I think audiences often take for granted the effort that’s put into TV/film production, especially when it comes to navigating between staying faithful to the source material and handling the constraints of the visual medium. As you’ve said, the mediums can’t be equally compared, and I think that when done well, both offer unique interpretations of the story they’re trying to tell. I’d argue, though, that Eragon’s a case where the book _is_ unequivocally better than the movie (they really butchered that adaptation, #SorryNotSorry )

I have to say that the banana allegory also made me laugh out loud in Wjinhaven, so I am loving this ongoing trend. But in general, I really loved this piece and the topic! I have always been an avid reader and have had this comparison in mind for quite some time. I think that when it comes to storytelling both mediums have the ability to create something great even if it’s through different techniques. What I like about books is that you can get really inside the character’s mind and follow their story in detail yet with movies it’s really the ambiguity that I love that is also difficult to capture in books. You can have several scenes in a movie without any dialogue and still get a rich amount of information. I also think that the reason people say the book was better than the movie is that they read the book first. I remember watching Gone Girl in the theatre and thinking it was the best movie ever which made me get the book and read it. Although the book was also really good, it was the movie I fell in love with as it was my first introduction to the story. So I think that is something to keep in mind when hearing that phrase.

First of all, I totally experienced this before, and it can be so annoying! I agree with you that when it comes to a film or visual imagery, we have not as much freedom for imagination as we might have when reading the words. I do think that when seeing a visual image we have freedom in another way, more of an emotional way. Most of the time a movie or an image creates a kind of atmosphere or mood that makes us react to it in a way. It is an intention from the filmmaker to might evoke a certain reaction with the observer. But the freedom can still be there, not through imagination or associations, but through our emotional reactions. Overall I think it was a very interesting blog and subject to read! Good job!