Written by: Akif Aliyev

The year of 2020 in many senses has been a year of reflection. Not just for me I believe, but for all of human kind, particularely those privileged enough to come from a background of economic and political stability. It has been a year of symptom accumulation of global problems swept for too long under carpets. Those problems have now mutated and re-emerged, but we have new tools to counter them. However the question is, are we using them correctly? Or has the web around us grown even tighter than before?

In recent history, social media has become an indispensable tool for activists all over the world. It provides individuals with the ability to reach audiences much beyond their immediate surrounding, it facilitates crucial information transfer in times of injustice and conflict, and when required, it provides much needed shelter and anonymity to those who risk their lives by speaking out on sensitive topics in sensitive places. In theory, it should be the activists dream tool, until 2020 exposed some major potholes.

The Uyghur crisis in China, the Black Lives Matter movements, the US presidential elections, the Yemen crisis, the list is endless. We live in a world where as far as human history goes, conflict has seemingly been second nature. However, the beauty of times today is that – even if flimsy – this might be one of the very first periods of human history that the basis of the international community has been set up with the intention of reaching and maintaining perpetual peace. Albeit, conflict still wages on in many corners of the world, but a very big step in curbing total war and mitigating security issues has without a doubt also been achieved. Only today this progress is put at risk by a new tandem enemy, slacktivism and misinformation; both inescapable symptoms of social media.

Slacktivism could be defined as a “low-cost, low-risk, and noncommittal” (Muslic, 2017) style of activist engagement which has become greatly synonymous with social media spaces like Twitter and Instagram. The Pro? It allows causes to gain a near viral status through mass surface level engagement of individuals around the world. The Con? Much like any other viral content, soon enough people get bored of it and move on, unfortunately often without making any impactful change. Slacktivism comes hand in hand with misinformation as probably the two largest threats posed to our human desire of perpetual peace, at least within the limitations of the internet and its effects on real life societies. Both phenomena boil down to the same root cause; social media apathy.

Essentially, social media has fostered a willingness within us to share content without deep prior analysis or thought, which is what today is being exploited at a global scale by various parties to spread selective disinformation. Sometimes it is to instigate a shifting in political opinion (such as with 5G and COVID-19 conspiracies), other times it is utilized to discredit or bolster certain political candidates (such as with the current US elections). No matter in which way misinformation is weaponized, the bottom line is that the tech companies responsible for our social media software know no better than anyone on how to curb the problem. These algorithms aren’t designed to define what constitutes true or false information, and in a time of such rapid and instantaneous information diffusion, it is almost impossible to devise a foolproof mechanism of control.

Coupled with slacktivism, social media has turned into a ticking time bomb. The algorithms which power our feeds, list our trending hashtags and decide who sees what are greatly influenced by “unprecedented levels of shares, comments, and likes” (Wardle, 2019). It is essentially a competition of engagement suited to a capitalist business model that decides which cause gets the most attention based off online interaction. In theory, this might seem like a just and sensible algorithm, but compiled with misinformation and the general apathy of most social media users towards the validity of information, it poses many exploitable shortcomings that can culminate in various forms of crises. As mentioned by Claire Wardle of the Scientific American, had these social media algorithms been “stress tested” (Wardle, 2019) for possible scenarios of crisis, it would have become much more evident to tech designers what social scientists and propagandists had already known; that humans in essence are evolutionarily wired to respond best to “emotional triggers” (Wardle, 2019) and are much more likely to engage with content that supports their preexisting biases and prejudices. Social media designers may have intended to curb this bias through facilitating deeper connection, but they overestimated the effect such connection would have on preexisting human tendencies.

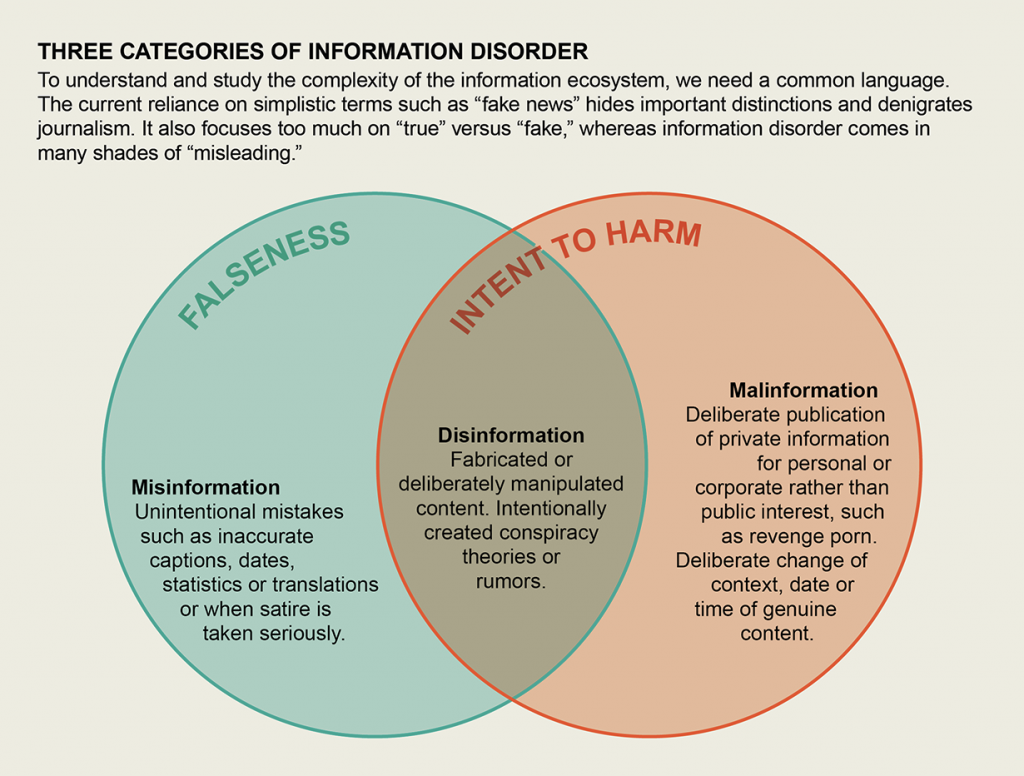

When the question comes to what can be done, it is first important to recognize that false information is not all intended to be malicious. As seen above in the visualization by Jen Christiansen, simple mistakes and typing errors, outdated statistics or misunderstood satire can also be seen as misinformation, however the situation becomes much more volatile when we are talking about false information intended to harm, known as disinformation and malinformation. These forms of false information consciously contain fabricated content, private information and manipulated truth with the intention to either further an ideological agenda or personal interest.

What to do? That is probably the toughest question to answer in this entire spectrum of problems. At individual level, it is crucial that we pay attention to confirming the validity of the information we share where and when we can. It is important to be able to view information objectively and without the influence of emotion. It is more likely than not that we surround ourself with information we would like to hear, rather than what is objectively true. This is easier said than done, but until a proper method of foolproof information validation is introduced by tech companies themselves, not much beyond the individual spectrum could be done. Such a system would have to function without silencing voices it deems wrong, but objectively being able to identify information that is in essence false. As this does not seem an early reality, it is crucial that we fix our own habits first, one at a time.

Sources:

- Wardle, Claire. “Misinformation Had Created a New World Disorder.” Scientific American, September 1, 2019. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/misinformation-has-created-a-new-world-disorder/

- Muslic, Hana. “What is Slacktivism and is it Even Helping?” Nonprofit Hub, June 20, 2017. https://nonprofithub.org/social-media/what-is-slacktivism-does-it-help/

Recent Comments