“To be ludic is not to be ludicrous. Play doesn’t have to be frivolous, although frivolity isn’t triviality; very often we ought to take frivolity seriously. I’d like life to be a game—but a game with high stakes. I want to play for keeps.”

From Robert “Bob” Black, “Abolition of Work”, 1991.

The concept of “play” has been grasping my attention step by step for several years ago. With my first job as a camp counsellor for teenagers and young adults, I started to learn how to design and articulate playful experiences as a means to engage, connect, and cultivate humans collectively. Usually, some group games will be the best way to break the ice between stranger team members, and competitive games are useful for campers to develop solidarity within the group. The relationship between children’s play and their development has already foreshadowed the value of studying play in my mind in terms of understanding the human mind and society, let alone there is also animal action of play which points to the bigger picture of understanding play as some kind of fundamental rule of nature in general.

However, compared to the traditional mode of physical play, the emergence of computers and the internet create new scenarios for the field of study. The issue becomes thousands of times more complicated than it used to appear. In the recent trend of building up metaverses, i.e. virtual spaces based on digital currency for people to interact, play and work, the keyword “play to earn” appears at the most core position in its cosmo-philosophy. Why the concept of play stands out as such a preliminary place for the virtual ways of dwelling? It definitely has something to deal with the nature of play in the digital world.

What are “play” and “playbour” in a digital age mean?

(*As a recall and developing of Big Media course on Big Play)

A systematic study of the ontology of play can be traced back to Johan Huizinga‘s Homo Ludens, which studies the role of certain types of play activities in human culture, i.e. leisure play which he refers to be free and not for certain utility. Under this framework, the concept of “play to earn” is definitely losing its core identity as a higher level of human activity of play. However, this conclusion is based on the presupposition that there is a clear categorical division between the nature of leisure play as futility and serious work/study or other forms of play for a purpose.

However, this line seems to blur nowadays. Digital play including computer and video games can be and usually is labour intensified and energy consumed, no matter whether the game is competitive or not. It might be played for leisure, but end up labour, due to much more complicated tools for play, i.e. the digital machine. This assumption of digitalization transforms our ways of leisure play dramatically in terms of interacting with a much more complex system, which is a process of from quantitative change toward qualitative change, is what I want to drop here. Also, the post-capitalism reality of the digital world decided that most of the games as products were designed for massive play and gaining more profit, then the player also shares the role of consumer for digital play. Purely leisurely play becomes almost a romanized and idealized concept, a lost utopian. It doesn’t mean that we don’t gain leisure and pleasure from digital play anymore, but transfer the nature of play from leisure to a leisure-labour complex. Empirically, digital play including computer and video games can be and usually is labour intensified and energy consumed, no matter whether the game is competitive or not. The post-capitalism reality of the digital world decided that most of the games as products were designed for massive play and gaining more profit, then the player also shares the role of consumer for digital play.

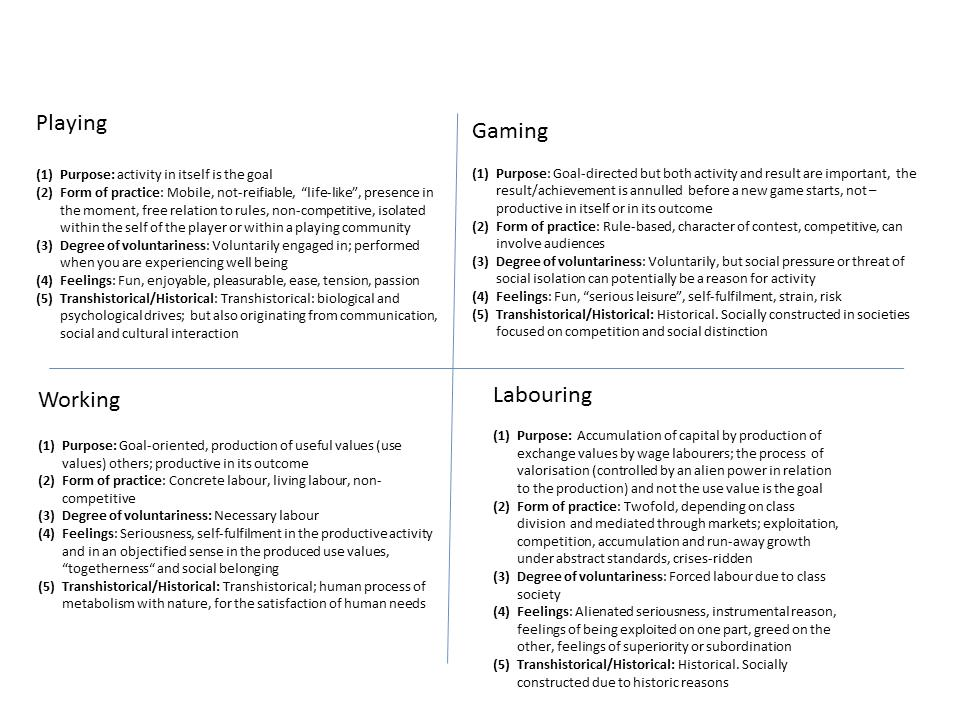

“Play” as an ambiguous umbrella term, includes many phenomena and activities with huge diversity as we learned from Brian Sutton Smith‘s Play and Ambiguity, which can be seen as an enumeration of all types of play and impossible to have any general study and explicit conclusion on their sharing nature. Huizinga’s method is to limit the range of study by defining a certain type of play, i.e. play as futility, and leave the rest out of attention. However, if we need to study the relationship between different types of play and their relation to wider social-economical issues, then a clear categorification and definition are required by convention. Based on Roger Caillois‘ distinguishing of play and game, Arwid Lund steped forward to a four-categories conceptual typology of play, game, work and labour.

and Relations, ‘Figure 2: The typology'”, 2014.

Kücklich introduced the term “playbour” in 2005 as a type of digital labour. Lund criticizes the implication of the concept of “playbour” and makes the categories extremely complicated based on his typology. To give some early examples:

- Modding in Minecraft: It can be understood as “playbour”, which is volunteers and for fun but without enough feedback relatively; but there are also professional YouTubers who make real profit out of the advertisement, here, play becomes content for creativity entering broader Post-marxism critique of the culture industry.

- Esports: it looks like the most mature way of “gamework” at first glance. But if examine closely, the unequal distribution between star players and normal players and other workers, as well as the long-term health problems of players and the general overworking phenomenon reveal the labour nature of the whole industry, which shows the implication and drifting between “gamework” and “gamebour”.

It is through this theoretical lens, that we are able to observe the new arising(from 2020) phenomenon of “play to earn” crypto games in the metaverse and other digital play platforms.

What is “play to earn” games?

From the level of product, “play to earn” is a concept and way of participation promoted by metaverse and other NTF-related and crypto-currency-based programs. As its literal meaning implies, this mode of participation guarantees both pleasure and utility —- earning digital money which can be transferred to real money. The economical study and critique have already come out right after the booming of it in 2021 during the pandemic when lots of people lost their job. As shown in the video below, the problems of play-to-earn crypto games include: the exploitation of the Global South labour, the fake promise of no risk due to the unstable price of crypto-currency and the danger of hackers, as well as the fundamental question of its unsustainable economic logic/model since the value of digital objects earned in those games can not be guaranteed.

Some critiques see below:

As one of the buzzwords, there is definitely a reason for people’s passion. And my interest is certainly about what makes this concept so fascinating in terms of what we understand about play, game, work and labour. Meanwhile, what makes it so problematic and dangerous intuitively from some people’s perspectives not in an economical and practical sense but a philosophical sense?

An interesting observation could be, why they use “play to earn” but not “game to earn”. Clearly, the concept of “play-to-earn” is a selling method for this merging concept of play and earning money, two pleasant modes of being together. However, the use of the concept of play which connotes voluntary pleasant participation is actually not true when the benefit is expected and certain rules are applied. The extra pressure and cost of play/game-to-earn rather than play-to-play were hidden behind the positive connotation of play. For the concept to earn, economical studies and critique above have already shown its nature of high risk, instability and global inequality which results in a type of playbour/gamebour for massive participants.

However, a buzzword already gains attention won’t just disappear easily. There are always people and institutions who are chasing a revision of the existing model and becomes the one who really achieves this concept. That’s why there are still tons of new crypto games created every week and new marks and videos are made to discuss the pros and cons and possibilities of it.

More than ten years ago, Eric Zimmerman wrote his famous Manifesto for a Ludic Century(2009). Lots of people do not take it seriously then. However, the world nowadays seems to show that we are heading toward that picture without a doubt——no matter if it is a better or worse world based on any criteria.

Recent Comments