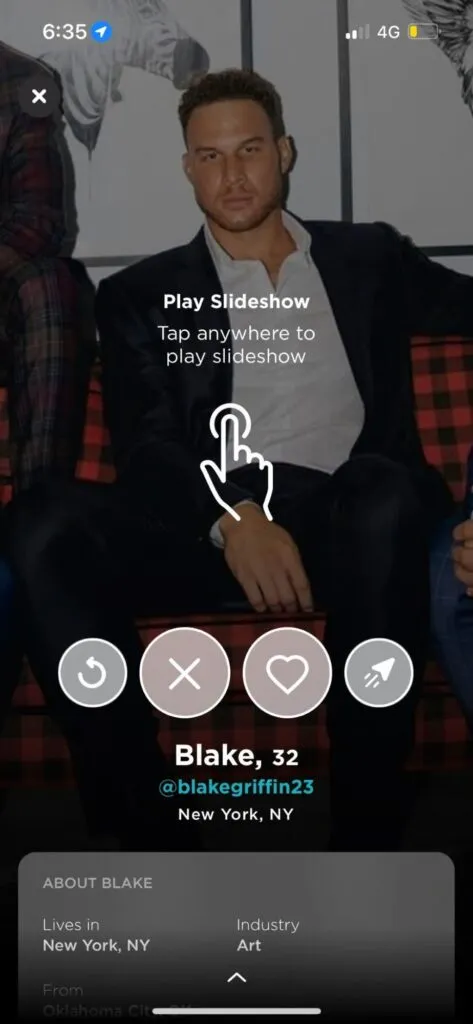

I joined Raya, and what I found was more “business” than “pleasure”. Raya is an exclusive dating app known for its selective membership. The process required referrals from two existing members, underscoring its commitment to privacy and exclusivity.

Eager to connect with like-minded individuals, I was excited to explore this curated community. Upon joining, I encountered a monthly membership fee of 20 euros. To enhance visibility and connect with a broader audience, additional in-app purchases were necessary. These costs, while not exorbitant, added up, prompting me to question the value of the investment. The user base predominantly consisted of Instagram influencers and celebrities. This focus limited the diversity of potential connections, as many users were more interested in status than forming meaningful relationships.

This dynamic is not isolated to Raya. Silicon Valley has long marketed itself as a hub of radical innovation, yet beneath the shiny promises of progress, it thrives on cycles of obsolescence and economic stratification. As Christine Finn writes in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, the region often replaces old technologies with new ones, but instead of dismantling social hierarchies, it reinforces them. Dating apps, much like the broader tech landscape, replicate this pattern by promoting visibility and status over genuine connection, creating platforms that profit from engagement rather than fostering authenticity.

Innovation or Exploitation?

Dating apps have positioned themselves as disruptors of social interaction. They claim to offer a faster, more efficient way to meet new people, powered by algorithms that match users based on compatibility. However, much like Silicon Valley’s broader tech landscape, these platforms often prioritise user engagement over authentic interaction. The swiping mechanic that drives many apps is designed to keep users hooked, not necessarily to foster meaningful connections. This business model makes it clear: the goal isn’t to help users form lasting bonds, but to generate engagement, turning digital interaction into a product.

The Business of Engagement

The underlying business model of dating apps reveals much about their true intentions. These platforms aren’t built to help users form genuine connections — they’re built to keep users swiping. Premium features like “boosts” and paid visibility ensure that some users are seen more than others, not because they are better matches, but because they can afford to pay for the attention. This system mirrors the monetisation strategies of Silicon Valley tech giants like Facebook and Instagram, which profit by keeping users engaged for as long as possible. In both cases, the emotional investment of the user becomes the product.

Are We Repeating Old Social Inequalities?

Dating apps are often sold as the answer to breaking down social barriers, yet the algorithms that power them frequently reinforce the same inequalities they aim to solve. Studies show that caucasians are grouped and receive more likes, the bias is embedded into the code. Instead of challenging the structures that define who we connect with, dating apps often perpetuate existing societal biases. This emphasises the critique of Silicon Valley itself, where “innovation” is often less about creating something new and more about repackaging old systems for profit.

A Step Forward or a Step Back?

The rise of algorithmic matchmaking forces us to ask: Are these platforms truly optimising for better connections, or are they simply designed to keep users engaged longer? Much like Adam Fisher critiques in Valley of Genius, the digital platforms of Silicon Valley have created monopolies that prioritise growth over equity. Dating apps, rather than revolutionising the way we connect, are using technology to further entrench patterns of engagement that favour monetisation over meaningful interaction.

Digital interaction may not be the utopia we imagined. Like Silicon Valley’s broader tech ecosystem, dating apps often sell us the illusion of progress while keeping us trapped in a cycle of engagement-driven algorithms and endless swiping. The question remains: are these apps truely designed to be deleted?

Recent Comments