It is a sign of our time – an era often referred to as the “information age” (Galloway, 111) – that media is generally understood as information. Think TV, Telegram or tabloid: whatever media one consults, the idea is always to receive information (in its most broad sense: content) be it the weather forecast, cat videos or academic research.

So information, etymologically deriving from Old French for “communication of news”, can be something that is given to us, as data, as an asset or an order, while not having to rely on the form in which it is transmitted. At the same time information is to be accessed and to be found, sometimes on a shelf, behind a paywall or the footnotes of an AI prompt.

With the internet as the “world’s brain”, where ideally, all existing information is made accessible (a utopian vision), it seems like gathering information and knowledge must be a simple undertaking.

Quite literally, the “search bar” seems to be key to every answer one could possibly be looking for, and with AI accelerating this idea enormously (“Ask a question”), it makes sense to believe we truly are in the middle of the age of information.

However, in the never ending stream of content, knowledge and truth seem to have became interchangeable terms for information. This becomes problematic when two sides consider their own information to be the only truth, and dangerous when they resort to means to give their own truth more power, because where fake news and technical manipulation (so-called ‘deep fakes’, for example) are used, ideology and populism are not far off.

But aside from global politics and world events, the search for truthful information in the digital age is also a difficult undertaking on a smaller, individual level.

Although we are all now aware that we should not automatically take online information at face value and even my grandparents no longer fall for every AI animation, the following example illustrates just how nuanced the transmission and dissemination of information in digital media can be.

The headline of the (by me digitally consulted) German Newspaper Stuttgarter Zeitung on Friday, September 26 (2025), was the following: “Drastic job cuts at Bosch”. (Bosch is one of Germany’s largest technology companies, particularly in the automotive supply sector, and a major employer.)

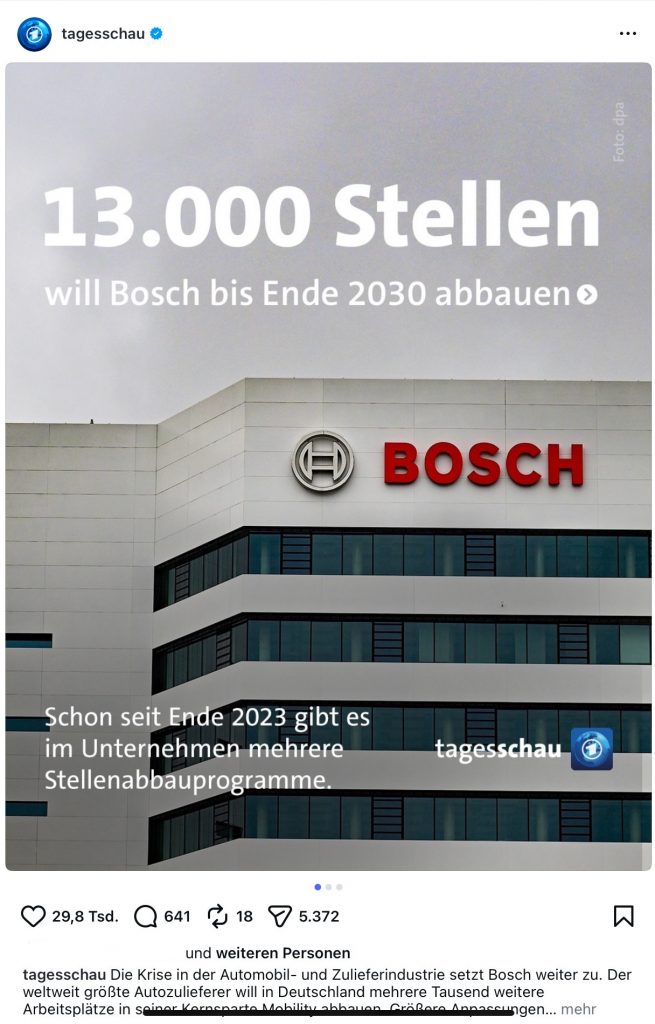

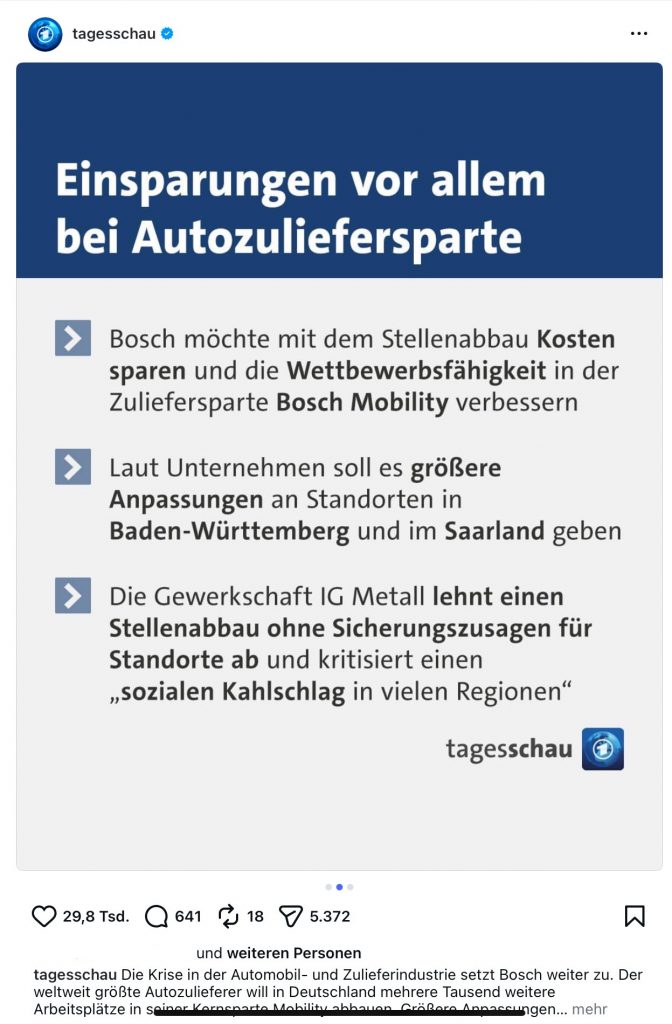

Correspondently, the public service news channel Die Tagesschau published a three slide post on Instagram with the heading “Bosch plans to cut 13.000 jobs by the end of 2030” on the same day.

While the newspaper article is a continuous text, mainly focusing and quoting reactions of appalled work councils and representatives (IG Metal and others), the Instagram post is a very condensed transmission of the issue in key points.

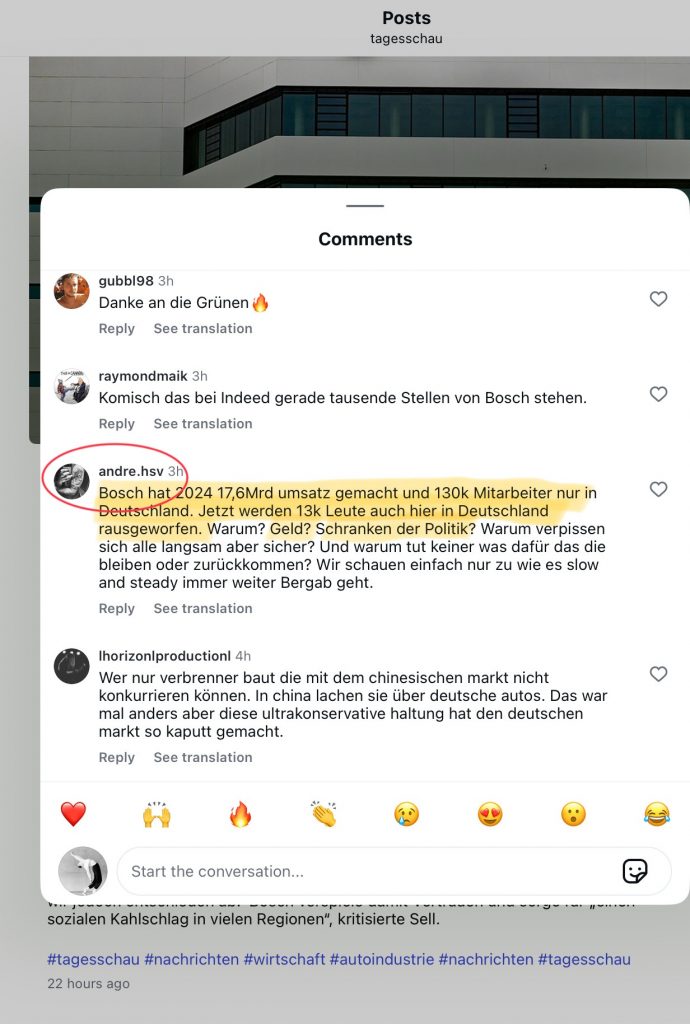

However, one could argue, the content of both article and post is the same, only the medium and way of transmission differs. A major difference however is then the reception of the two information sources. While the newspaper article is followed by a comment of one author writing under his real name (Klaus Köster, economist with a university degree, according to his LinkedIn biography), the Instagram post can showcase the reaction of all readers in real time, through likes and plenty (angry) comments.

Comparing Kösters comment and the ones in the Tagesschau post, what counts as more information here? Is a digitally published written word enough to be considered information?

Can it possibly be truth without being backed up by sources? Then however, we had to argue that both the newspaper article and the post fail this criteria, because they also both don’t state their sources. It might seem like there is an inherent trust in specific news outlets, especially the printed press, while digital content quickly becomes opaque and untrustworthy.

Logically, the next step in finding out more about the issue would still be an online search. Without surprise, typing in “Bosch” in my search engine, “job cuts” is directly the first search suggestion. (Here it might be interesting to be using a browser that’s default setting is not German language, for it is clear that the suggestions and results would be different.)

The search of “Bosch job cuts” in Google news lists firstly 4 major German news outlets, one of them being again the Tagesschau and then Bild, which is a tabloid. Three headlines or openers state again the number of 13.000 planned cuts, the language varies from neutral to emotional (“drastic”, “bitter cut”).

If one searches up “Bosch job cuts”, so the exact same term, in the browser “DuckDuckGo”, the first 4 news results are similar, however not identical: the Tagesschau appears again, however with a different, slightly older article, the Bild article doesn’t show up at all and instead two online magazines.

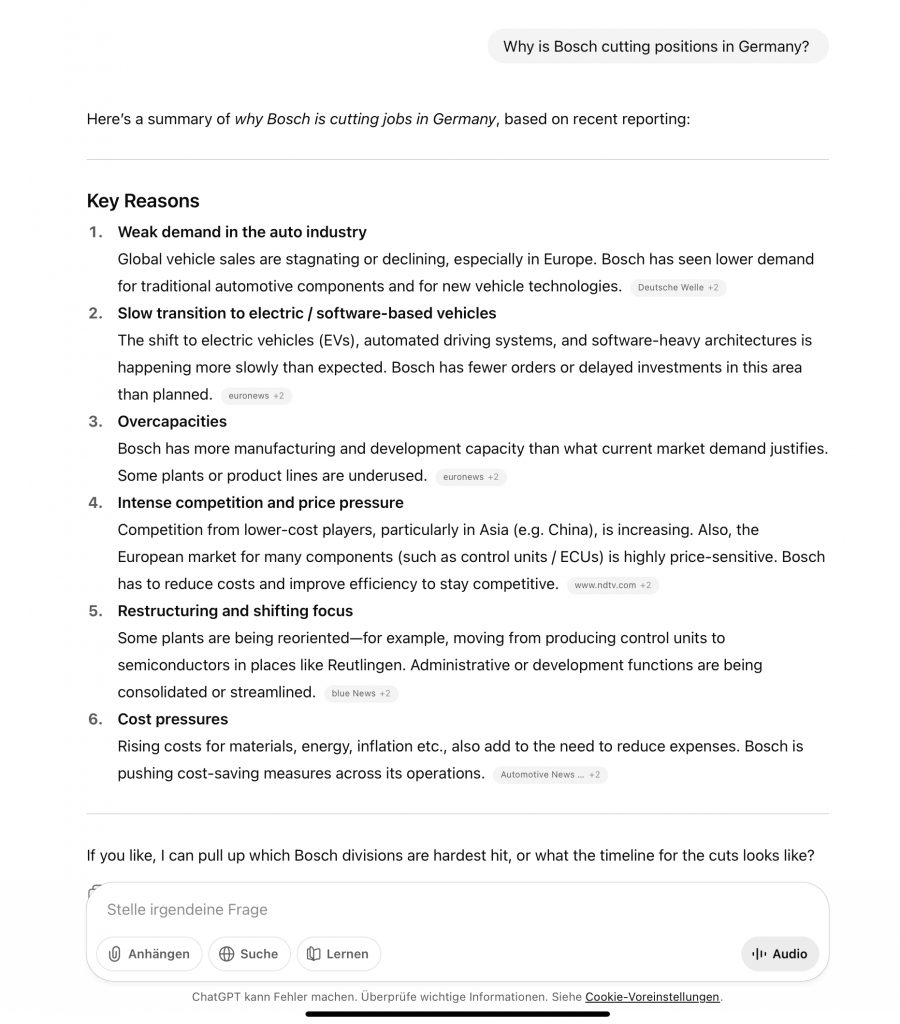

A similar effect has the further search of the topic in artificial intelligence engines: asking both ChatGPT and perplexity the same question, “Why is Bosch cutting positions in Germany?”, leads to very different answers, also depending upon which language (German or English) I use for the prompt. Again, the content might not differ – and admittedly, I choose a topical issue that comes with factual information and little controversy on purpose – but the way the content is listed, phrased and backed up. Both ChatGPT and perplexity address and even directly link their sources, but they are again very different. Perplexity for example uses the official press release from Bosch as their first source, which isn’t mentioned at all by ChatGPT.

The press release by Bosch might seem like the closest one could possibly get to the root of the story I assume, reading the statement however, it’s naturally very carefully crafted, with apologetic tone and euphemisms (“particularly far-reaching adjustments” sounds a little better than “13.000 job cut”, no?).

Another interesting example is looking up “Bosch” in academic library catalogues – which has been taught to us at University as the reliable source. And again, depending on which one I use, Leiden’s library or the catalogue of the German Goethe University in Frankfurt, the top results of Leiden all refer to the artist Hieronymus Bosch, while the third result of Frankfurt is the annual business report of Bosch (the company).

Last but not least, I decide to return to Instagram and look up Bosch Germany’s account, thinking they’d maybe posted a statement or something, but all I can find is a pretzel related survey (it’s the opening weekend of Oktoberfest after all I guess).

In summary, it can be said that this is less a journalistic investigation with surprising results and scandals, but rather a good representation of what searching for information digitally means.

Depending on (financial) interests, readership and medium, there may be one truth, but never just one answer. I realise that it is not so much me sitting in front of my device finding and processing information, but rather the content and answers finding me via digital media, in a targeted and calculated manner, depending on which digital sphere I am moving in.

It is therefore more important than ever to remain critical, including of the way in which information finds us online and why.

Sources:

- Galloway, Alexander R. Protocol : How Control Exists after Decentralization. Cambridge, Mass [etc: MIT Press, 2004. http://digitool.hbz-nrw.de:1801/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=1914610&custom%5Fatt%5F2=simple%5Fviewer.

Thank you for sharing this insightful information. I don’t know much about this company since I am from a different country, but it’s fascinating to see how the results can vary so much between AI tools. It reminds me of my internship experience, when I asked people what they thought about AI language models. Many of them mentioned that, since these models are trained differently, their outputs will naturally differ. Because of this, news can sometimes become more controversial, as certain information may be blocked online. For example, in China, there was a recent case involving the reported murder of a famous actor, Yu Menglong. When people asked a Chinese AI about it, the model responded as if the event never happened, while other AI tools showed results. This suggests there may also be political reasons behind these differences. That’s why I believe we, as humans, need to gather information from multiple sources rather than relying on just one.