Proxy protesting: a concept I wasn’t familiar with. Last month I went to the exhibition Design and Disability at the V&A Museum in London. It was thought-provoking and shed light on various aspects I’ve never paid attention to. However, I was surprised with the use of technology throughout the exhibition, even seeing one of my recent favorite games, Unpacking, being used as an interactive feature.

It was also interesting to see Tiktoks in a museum exhibition. The curators showcased social media posts featuring “disability hacks” on screens, highlighting the power of online communities and shared knowledge. Seeing social media presented as a museum artifact felt unexpected, but also fitting, as it is part of our everyday lives.

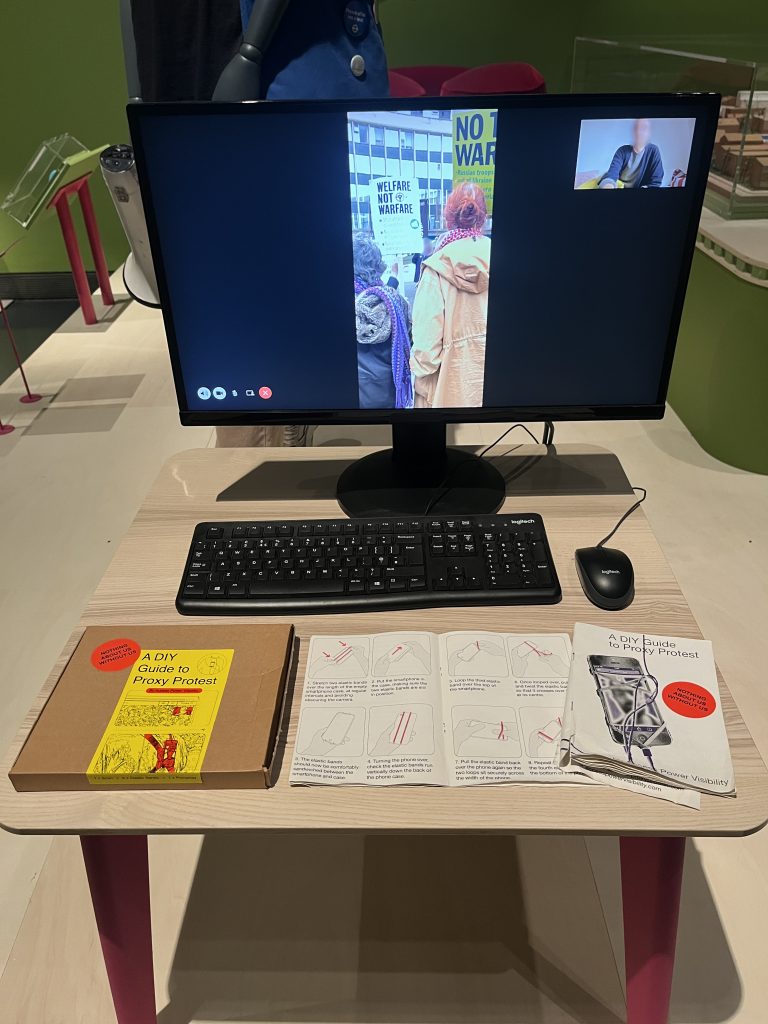

What surprised me most, though, was encountering a concept that truly felt like a discovery: proxy protesting. I may be living under a rock, but I had never come across the term before. Learning about it reframed how I think about activism and participation, particularly for those who are unable to protest physically due to disability or other barriers.

The exhibition made it clear how technology and social media can act as powerful facilitators of political expression. Digital platforms allow voices to be amplified, stories to be shared, and causes to be supported beyond physical limitations. Through proxy protesting, individuals can participate in protests without leaving their homes. In this way, technology not only broadens access to political engagement but also challenges traditional ideas of what a protest looks like, making activism more inclusive and collective.

The official website recommends WhatsApp as a reliable messaging app with end-to-end encryption, offering additional layers of security to protect those involved. While WhatsApp is a platform I often associate with politics, I usually think of it in a very different context. In Brazil, for example, it was widely used during elections to promote candidates through group chats and mass messaging, violating the platform’s terms and conditions. You can read more about it in this BBC report, which I won’t focus here as it is not the main point of my blog.

What I want to reflect on instead is that these platforms can be re-signified and repurposed in multiple ways, responding to very different kinds of needs. They can be empowering, but they can also be misused with harmful intentions. On a more hopeful note, the digital world can be a powerful space for accessibility, expanding participation and creating new possibilities for inclusion.

Recent Comments