My grandfather enjoys sharing social media articles with our family chat group. These articles typically have titles such as “Shocking,” “Breaking News,” or “Latest Update.” Most of them talk about health advice, stock trends, family relationships, science explanations, or national policy. But when you actually read these things carefully, they all seem questionable. Some of the health articles contradict basic medical knowledge. The relationship advice often feels outdated and out of step with current values. The science and policy pieces are full of invented claims that are hard to take seriously.

Those of us in the younger generation usually ignore these messages. We know the information is false, yet we cannot convince my grandfather, because we judge information in completely different ways.

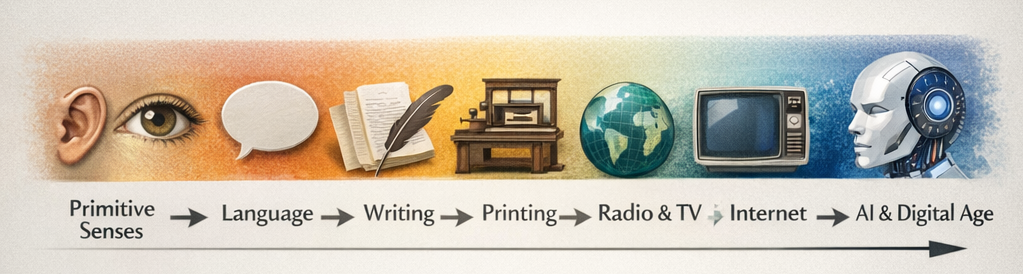

Where do people get information? At first, humans relied on sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, which meant information was limited to the present moment. Later language allowed people to receive information from others and pass it down across generations. Then, writing and paper created books and newspapers, making it possible to preserve information and transmit it over long periods. Finally came the age of electricity and digital media. Through radio, television, the internet, search engines, and AI, the amount of information a person receives has grown exponentially. People are constantly surrounded by distant information and nearby information, true information and false information, all arriving at the same time.

But which information do we believe? People floating in this ocean of data are always trying to confirm what is real. Different social groups gradually develop their own methods of judgment, and these methods usually depend on identifying a reliable authority.

Different generations and social circles have different standards for recognizing authority. For my grandfather’s generation, which grew up before the information explosion, academic experts and official state media are often treated as trustworthy sources. A short video creator can gain instant credibility simply by wearing a suit and sitting at a desk that looks like it belongs to a government office or research institution. For people who grew up during rapid economic expansion and media saturation, popular influencers or business leaders often become shortcuts for judgment. Younger audiences shaped by deconstructionism and internet culture may trust narratives that feel personal, informal, and close to everyday life. When deciding whether to trust information, we often look at who is speaking before we look at what is being said. In an age of information overload and cognitive fatigue, this low-cost trust mechanism is extremely attractive.

This system is powerful because it relies on a basic human instinct to read signals. Suits, polished office settings, staged bookshelves, technical jargon, and titles like “Doctor,” “CEO,” or “Senior Specialist” act as visible authority signals. They are not the same as truth, but they can cheaply create the illusion of credibility. More subtle signals come from platform design. Pinned posts, trending lists, recommendation slots, verification badges, and visible counts of shares and likes to compress complex social validation into a simple ranking system. These features function like default settings that quietly guide our judgment. We believe we are choosing freely, but our decisions are shaped by structures of visibility.

The digital age, and especially the AI era, has produced an even harder form of authority to recognize. It is an authority without an owner. Search engine summaries, aggregated accounts, and AI-generated rewrites produce text that contains content but loses a clear source. These messages do not feel like a specific person or institution speaking directly to you. They feel like a puzzle assembled from many fragments. The audience does not matter. Speed of response matters. As a result, the question of who said it disappears, while the platform or model itself becomes a new form of endorsement. We mistake the channel for the source. This creates a paradoxical authority. The more anonymous the information is, the more it resembles universal knowledge. The less accountable it is, the more neutral it appears.

The real problem is not that people believe in authority. The problem is that our information environment structurally requires authority. Faced with overwhelming data and limited time, trust shortcuts become a rational form of self-protection. No one can verify everything, and no one can slow down forever.

So, what can we do?

Instead of rejecting authority, we can build a more practical way to evaluate it. This returns us to the old question of tracing information back to its origin. For me, three simple checks are enough:

How does it know? The focus should be on method, not title. A claim that provides sources, processes, and evidence is more trustworthy. If identity and tone are the only support, and there is no data or explanation, then distance is reasonable.

Who does it speak for? Every piece of information carries motivation. Media needs traffic. Companies need profit. Institutions need influence. Individuals need attention. Understanding motive does not automatically invalidate a claim, but it tells us how cautious to be.

Who is responsible if it is wrong? Reliable information systems allow correction and accountability. Statements that can be revised are often more trustworthy than personalities that claim permanent certainty. A system with open discussion and revision history is usually closer to reality than a polished final answer.

Putting these questions into daily life leads to practical changes. We may become more willing to check sources instead of relying on screenshots. When hearing that “experts say,” we might look into the expert’s background instead of accepting the label alone. When using search engines or AI, we treat answers as starting points rather than conclusions. Reliable information depends on transparent evidence, stable correction mechanisms, and openness to discussion. We need to shift trust from who is speaking to how the claim is produced. Very often, truth is a process, not a sentence.

Recent Comments