It started with reading Edgar Allen Poe’s The Man That Was Used Up, mentioned in last week’s lecture on cyborgs. The short story tells of a general who is celebrated by the American military for his role in the forced displacement of Native American populations. The story’s epiphany reveals that the general is entirely made up of prostheses, having lost all his biologically human parts over the war. The title suggests that, with the loss of his human body, the cyborg-general has lost some fundamental part of his humanity, or soul. Furthermore, in situating this tension of man vs machine within the context of American military aggression, Poe has drawn a parallel between the two; the perfect war machine is not a man but a cyborg. It is a subtle but noticeable critique of the lack of humanity of these American war campaigns – only a robot could be capable of it.

[T]he figure of the cyborg might be reinterpreted as a version of Leviathan, in the sense of Thomas Hobbes, who defined the figure of the absolute ruler (Leviathan) as an artificial man with an artificial soul.

Takayuki Tatsumi, Full Metal Apache: Transactions Between Cyberpunk Japan and Avant-Pop America.

Poe wrote the story during the rise of industrialisation, which provoked anxieties about the loss of jobs involving manual labour. In The Man That Was Used Up, there is a question of what roles or trajectories will masculinity take in a robotic age where brute force is no longer only a human ability?

Alternate ending: the West has fallen

I want to introduce the idea of techno-orientalism here, as it has some resonances with the fear of masculinity becoming redundant in a technologically-advanced future. In the case of techno-orientalism, however, the fear is that the entire West will be replaced or made dystopian by East Asian economic expansion and technological superiority.

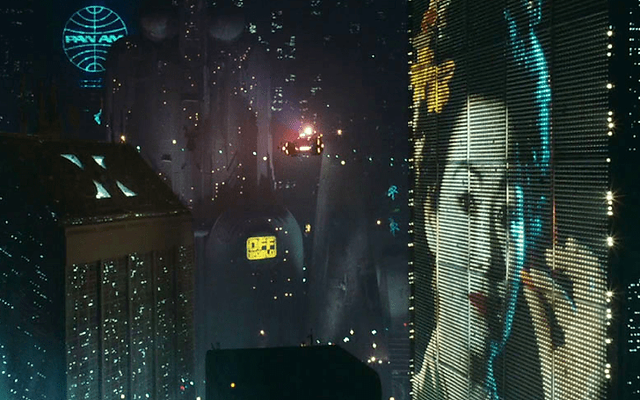

While cyberpunk’s aesthetics often draw from non-specific East Asian cities, I don’t want to flatten this to simply ‘cyberpunk bad’. It’s important to recognise the artistic debt many Western cyberpunk/cyborg narratives have to works like Akira (1988), which takes place in a neo-Tokyo and inspired film-makers globally. However, issues arise when Western cyborg narratives use the aesthetics of a decontextualised pan-Asian city, in which an apocalyptic story takes place, equating Asianness with a fallen West and a low quality of life. Usually, these stories have few Asian characters and instead centre white male protagonist-heroes – see Neuromancer, Bladerunner, etc. If these narratives include Asian characters, they are likely to be depicted as robots and are often highly sexualised, hence the trope’s tagline by Jane Hu: ‘where the future is Asian, and the Asians are robots.’

Where does this trope come from?

Techno-orientalism is usually understood as arising from Western anxieties about Japan’s economic boom in the 1980s. Under techno-orientalism, these fears about the superior manufacturing of Japan correspond with the dehumanising of Asian bodies into robotic entities, mimetic of the products that Japan’s factories were actually making. Therefore, in these Western cyborgian films, Asian people are depicted as artificial, intrusive and lacking the ‘humanity’ of the white characters who inhabited these films. I think that’s why this trope is important to highlight when we talk about cyborgs and cyberpunk, as we have often done in our class. Relating to Poe’s The Man That Was Used Up, ideas about who has a ‘soul’ or humanity are always relating to the fears of the contemporary culture. As much as I love cyberpunk, the history of the genre has a basis in an ideology of xenophobia and latent Western anxiety of no longer being the dominant culture. That’s not to say every piece of media that engages with cyberpunk propagates this ideology, and I enjoyed the film After Yang, which subverts aspects of the trope.

Ultimately, I see The Man That Was Used Up as distinct from techo-orientalist narratives, because in Poe’s story, the aggressive expansion of the West is criticised through the figure of the war general/monstrous cyborg, whereas techno-orientalism is all about the anxiety of losing Western dominance to East Asian growth. However, both ideas explore the nature of the cyborg body and its soul, and which social groups are dehumanised based on the socio-political context. I’m really interested to hear what you think and if you have any examples of the trope in action – or maybe you completely disagree or you have a great film recommendation to do with the genre. I just remembered this extract, which is from an unrelated text about an art exhibition, but I think it has some resonance with how some cyborg stories make superficial aesthetic choices that may have dehumanising ideologies:

However, exoticism is not necessarily inherent in the works themselves. It is in their decontextualisation, not only in the shift from one culture to another (which is inevitable), but more importantly, in the displacement from one paradigm to another; this has emptied them of their meanings, leaving only what Fredric Jameson calls a ‘play of surfaces’ to dazzle the (dominant) eye.

Rasheed Araeen, “Our Bauhaus, Others’ Mudhouse”

Sources

Betsy Huang, Greta A. Niu, David S. Roe, Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media.

Jane Hu, Where the Future is Asian, and the Asians are Robots

Takayuki Tatsumi, Full Metal Apache: Transactions Between Cyberpunk Japan and Avant-Pop America.

Stephen Meyer, Manhood on the Line: Working-Class Masculinities in the American Heartland.

Rasheed Araeen, “Our Bauhaus, Others’ Mudhouse.”

Thank you for writing about this subject! After reading your post, I now realised how often East Asia, especially Japan, is depicted or shown on TV when they depict a future with hovercrafts, holograms, cyborgs etc. And the fact that this idea is rooted in xenophobia and exoticism really amazed me, again thank you😊. The movie that dawned on me after reading this, was Ghost in the Shell. HOWEVER, I’m not quite sure if it fits into this trope as I saw it a long time ago.

thank you so much for reading! and thanks for bringing this movie up!! I think ghost in the shell (the 2017 movie because it’s based on a bigger Japanese franchise) definitely could be analysed from a techno-orientalist perspective, because of the dystopian implications of the setting which looks reminiscent of Hong-Kong. it also features celebrated asian actress, scarlett johansson … but that’s maybe more whitewashing than techno-orientalism ?

Very intriguing piece. Decontextualisation and exoticism are indeed the problem with cyberpunk, but it is certainly not limited to cyberpunk! Actually the game Cyberpunk 2077 is the perfect example of this: random Japanese words running around Night City, one that is situated in California (although the environment designer is a Japanese).

However, a sad remark is that Hong Kong indeed is indeed a cyber punk city at its finest with a system that is run by a near-dystopian capitalism.

Very interesting piece! I never heard some of these terms before and you explained them very well. I indeed never noticed that it’s mostly Asia that is depiced when we see cyborgs in movies or series.

Also I started thinking about the example of the soldier that had robot parts. It really makes you question: what makes him less human than others? and what make us more human?

A metafor you can think about is the one with the ship. If you build a new boat from the same parts, is it still the same boat? Maybe you know it.

I don’t explain this very well. But makes a robot arm or leg us less human? The line between human and machine is very interesting to me 🙂 so thank you again

How the socio-political situation is often absorbed into the image in a really subtle way is really intriguing.

Reading this blog, I realized how I see the East Asian city (as an Asian) is really different from how it is depicted in Hollywood cyberpunk films.

As you said. when the image is separated from its original context, it to the distortion of meaning and becomes mere aesthetic elements.

In so far as I learned, the images of the skyscrapers and somehow ‘futuristic’ aspects of East Asia are the results of rapid economic growth, which many East Asian countries went through to catch up with the ‘modernization’ over the course of the 20th century.

With the question of why this high-tech city occurred and what it results in current society, on some occasions, these aspects are also depicted as a dystopian future by East Asia as well.

However, the problem of Cyber techno orientalism here is more due to what these films show merely mirroring how the West sees Asia.

Thank you for this article!

This article makes me think a lot about how East Asia and the whole socio-political aspects around their “futuristic” cityscape are edited and reduced into stereotypic images 🙂

* it to the distortion -> it distorts meaning

(Sorry just found my mistype!)

Thank you for writing this post. I always find it interesting to see those techno-orientalism elements in media representations. What’s more interesting is how some Asian in our own community are fond of this representation. Still, it is up to individuals’ ideology and interpretation, and I notice that many people never get negative thoughts (such as de-humanized Asians) when they are big fans of some sci-fi works that are based on imagining an Asian futuristic landscape. But, it is also the reason that makes me think about the “invisible racism”. For example, in the Fukushima accident, I noticed how Western newspapers portrayed the calmness of the Japanese and how organized they were. Well, it is very obviously not real, and the dehumanized portrayal is to some extent, racism. The horror of racism is not how the hegemony harms “the other” by using armed force but the gaze of misunderstanding and making so much differentiation that making “the other” seem alien to them.