The art world is no stranger to the increasingly rapid, and brutal, trend cycles of the digital age. Nonetheless, the desire to stick to our centuries of artmaking tradition has rendered the sudden entrance of the digital consistently controversial, provoking heated and seemingly unending debate.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, it was a pioneering wave of digitally based artists who gained traction. Rising to notoriety in the early 2000s, American artist Cory Arcangel used tools such as old video games, photoshop and other software to create video and performance art. Perhaps Arcangel’s most famous work, Super Mario Clouds (2002) is a continuous multi-channel video installation created by modifying a Nintendo Super Mario Bros 3 game cartridge.

Erasing the game’s original landscape, Arcangel left nothing but the pixelated Nintendo clouds floating along the bright blue sky. The piece was presented at the Whitney Museum’s Biennale of 2004.

If Arcangel’s artistic practice may have seemed like frivolity to some, the Whitney’s exhibition catalogue made sure to emphasise the artist’s ‘rigorous conceptual approach to the use of computer hardware, programming languages, and the relationship between humans and machines’. The mainstream success and acceptance of digital artists like Arcangel demonstrates how digital mediums had been welcomed, and indeed celebrated, by the upper echelons of the contemporary art establishment. Here, the use of the digital for artistic output was promoted as a new, and exciting, frontier of creativity – the art of the future.

But what if an artwork was irrefutably tied to its digital footprint, unable to be traditionally shown a gallery or museum? Is it art if it can’t be exhibited? Or just another file on someone’s hard drive? While Arcangel’s artistic craft may have been new, he still adhered to a central norm of the art world – ensuring his digital work was translatable into the physical exhibition space.

Nearly two decades after the presentation of Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds, the unstoppable force of technological innovation has produced just that: the NFT. As explained by Irina Lyubchenko, put simply the non-fungible token (NFT) is a time-stamped one-of-a-kind and totally unique file. The encryption used for NFTs, known as blockchain, was created in the early 1990s and became popular through the emergence of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. In the mid 2010s, artists such as Kevin McCoy saw blockchain technology as a unique way to protect the rights and sales of digital artists.

Academic Lyubchenko perfectly summarised the role of NFTs in a digital world, stating that: ‘as a technology, a non-fungible token can create digital scarcity in an otherwise infinitely replicable digital space’. The ability of blockchain presented the opportunity to guarantee control over digital art sales in an otherwise unstable market. Just like a forged painting, a copied file out of the control of the artist would be deemed inauthentic.

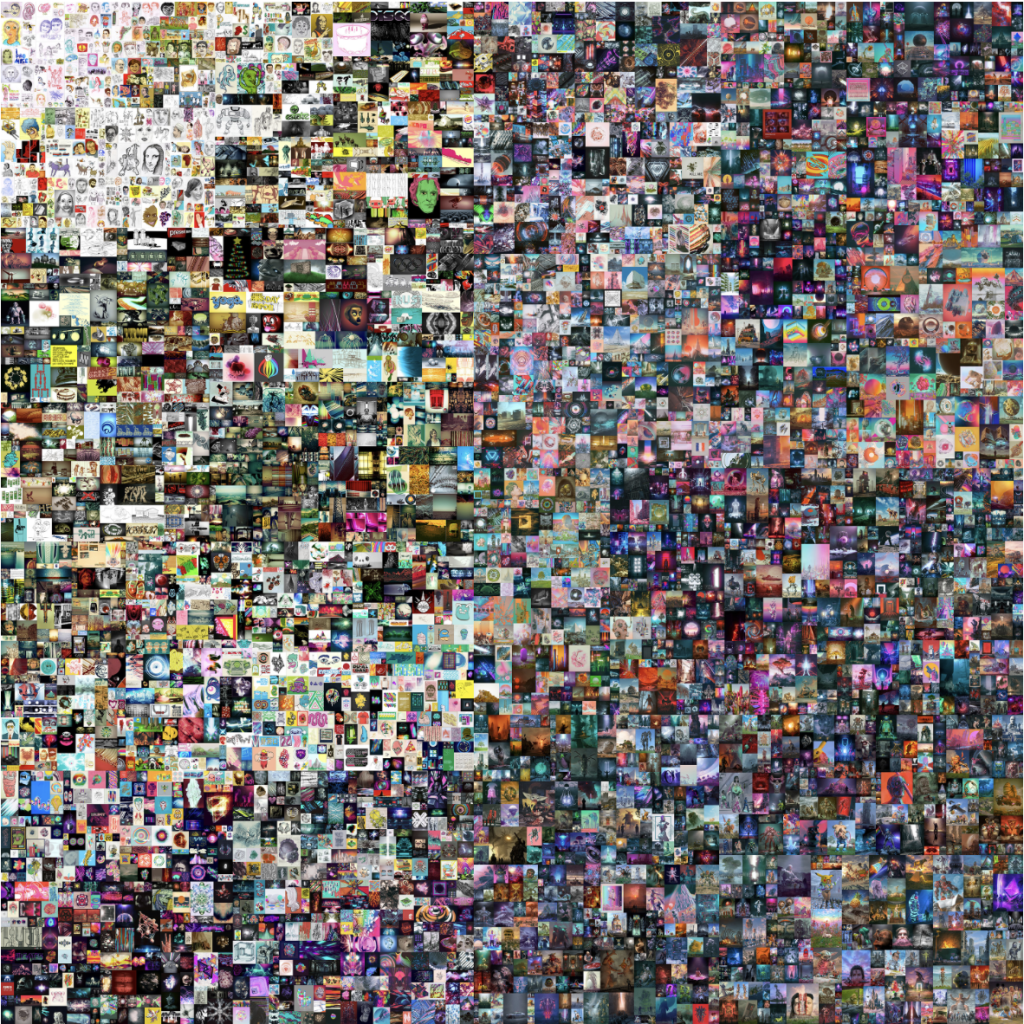

Following the monumental $69.3 million USD sale of digital artist Beeple (Mike Winkelmann)’s digital collage The First 5000 Days, NFTs quickly became a hot topic both in the cloistered world of art society, and mainstream culture. Art giants began to demonstrate interest in the NFT market, as demonstrated by the industry-leading auction houses Christie’s 3.0 site and Sotheby’s dedicated NFT auction department.

While the high-end players of the art industry have invested in the NFT market, its ability to infiltrate mainstream audiences remains to be seen. Take the Museum of Modern Art’s showing of digital artist Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised in February this year. Whilst crowds were drawn to the mesmerising colours and patterns of Anadol’s work, the gift of an added NFT to visitors drew little interest.

In a space where the public gathers for the enjoyment of the unique visual, tactile, and physical, what place does something as abstract as an encrypted file occupy? The work of artists like Cory Arcangel struck a chord with public audiences, able to toe the line between the abstract nature of the digital and the tangible experience of viewing an artwork.

The NFT may gain traction and hype in the realm of wealthy collectors, but its potential to become anything other than a talking point amongst public gallery-goers seems to fall flat.

I really enjoy how this post tracks the history of NFTs back to the beginning of digital art. It feels like it is important to emphasize the value of non-traditional art within the contemporary art debates (especially considering the time when this form of art-making wasn’t as apparent as it is today). Also, I liked the comparison of NFT art to a file on someone’s hard drive:) It shows the kind of privacy alongside the paradox of non-exhibitable art (something I haven’t considered that much before).