Conversations on the impact of AI in the workspace quickly veer into fears about job losses and mass unemployment. To start off, let’s take a moment to think: could it actually be a good thing if AI takes over our jobs? Picture a world where AI handles many routine tasks, like data entry, organising or planning, freeing us up to spend more time with loved ones, volunteer work, or hobbies. Sounds nice, right? But, in my view, also unachievable for the most of us.

It’s undeniable that AI is starting to replace certain jobs. Companies like Duolingo have opted to lay off staff and decided to rely more on AI-powered tools. Yet, despite these changes, the ongoing automation trend hasn’t led to mass unemployment. In fact, as I discussed in my last blog with respect to the translation industry, AI may actually create new job opportunities. After all, human supervision is still essential for tasks like post-editing and quality checks, especially but not only in languages that AI struggles with.

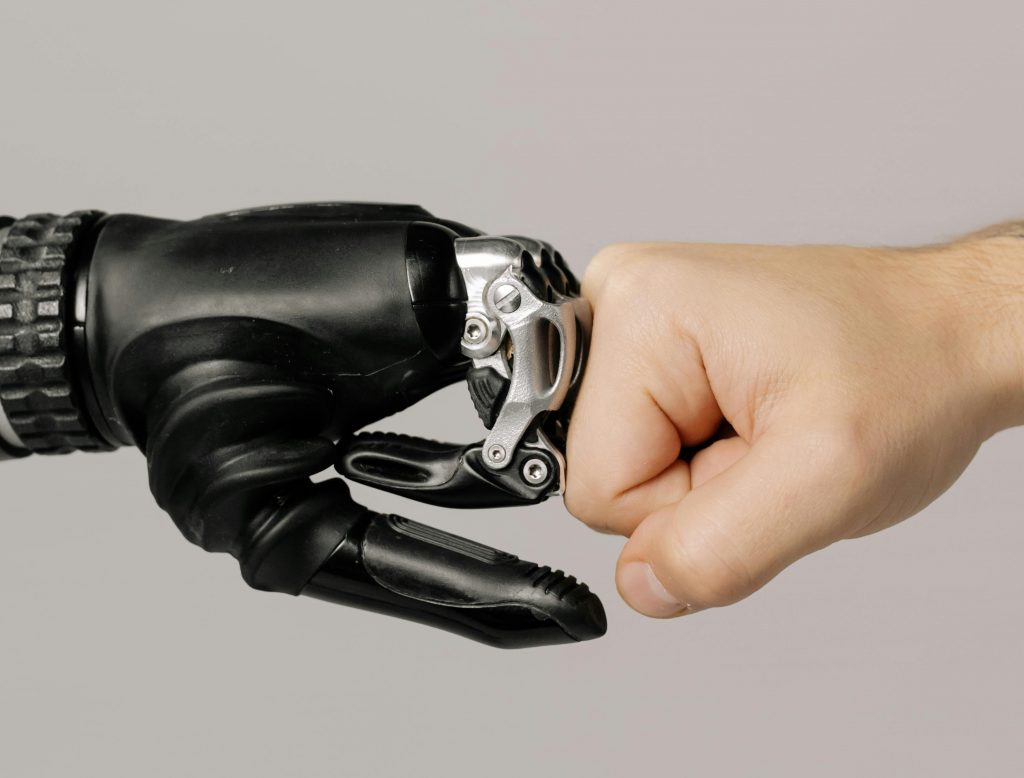

To broaden our view, recent UN reports (this and this) provide us with some encouraging insights. They suggest that AI is more likely to complement our work rather than to substitute it entirely. Hence, while some tasks may be automated, many jobs will still require the ‘human touch’. Also, if a job can be automated, it doesn’t necessarily follow that this actually happens. But if so, tasks taken over by AI are often repetitive and routine. This might in turn allow us to focus on what makes us human: our interpersonal, social, and emotional skills.

However, the UN reports also point to serious issues. Clerical jobs are most likely to be replaced. As women are overrepresented in these jobs, they will have to deal more with the negative consequences of AI, which could hence further aggravate existing gender inequalities. Moreover, access to digital tools and high-quality education is far from being granted to everyone. As economies shift toward AI-driven innovation, those without the resources to acquire digital skills are at a serious disadvantage, and it might become increasingly difficult for them to catch up. Take the example of farmers using AI to monitor their fields, manage pest control, and predict weather and market prices. For them to use AI effectively and to their benefit, they must have profound knowledge on how to use these tools properly, and they need to be confident in engaging with technology. Especially for those who haven’t had much exposure to it yet, that can be a big hurdle. And, by the way, this does not exclusively concern developing countries: many people in highly developed nations also feel overwhelmed and left behind in the digitalisation era.

The example of the farmers also shows that AI isn’t just about replacing jobs – rather it’s about augmenting existing roles. So, our biggest worries about AI mustn’t be about losing jobs. We should rather be concerned about how work itself is changing. Workers regardless of sector should be assisted during this transformation: they have to adapt to new roles, might have to take on new responsibilities while having machines assist them in others. Besides, we also might want to think about whether we want certain jobs to remain strictly human. After all, who’s accountable if AI makes a mistake or causes harm?

Finally, we must not forget that the outcome of the rise of AI is not predetermined: We, humans, still have the power to influence and control to what extent we let AI impact our lives. And policymakers have the responsibility to make sure that AI benefits us all – in the workplace and elsewhere.

In my humble opinion, I think this is a recurrent pattern in human history that must be examined otherwise. First, with the advent of the machine on the verge of the Industrial Revolution, people prophesied that the machine will eventually replace the farmer. Next, with the introduction of robots, people predicted that the robot will replace the worker. And now people are talking about AI replacing clerks. But is it?

Well, I don’t really have the answer, and I’ve been searching for data from the League of Nations to complete UN data and to look into the changes in proportions of farmers. It is well known that the proportion of people living in rural areas tends to decrease, this does not, however, reflect the promotion of farmers. I could not proceed with my research due to many complexities. When it comes to robots, I haven’t even started assessing the situation.

But when it comes to AI, I guess now that AI is more popular and prestigious than ever, more employers and employees alike will be more than inclined to incorporate AI in their daily lives. Note that AI is a very old concept made popular by OpenAI/ChatGPT, so nothing new. But now that AI is the big prestigious thing, more people will be attracted to it not knowing why. Who knows, AI may not remain as popular as it is right now. Compare VR technology made popular in the 80’s, loosing their popularity in the 90’s and early 2000’s, and now rising again due to an intense marketing campaign led by Meta’s Zuckerberg.