In today’s digital society, we grant countless apps and websites permission to collect personal data. Personally, I have given Google Maps permission to track my location, and as a result, I receive a monthly overview of the places I’ve visited and the kilometers I’ve traveled. While I am aware that this data is not entirely private, I choose not to dwell on it too much. In fact, I secretly enjoy the monthly summaries too much to care about my data being sold. As the saying goes, ignorance is bliss.

The phrase “data is the new oil” is often used to highlight the value of personal information in the current economy. Just as oil was the driving force behind the Industrial Revolution, data is said to be the fuel of the digital economy. As users, we are aware that these free online services come with hidden costs. It is clear that someone benefits from this exchange, and it is not the users. Still, knowing this hasn’t made me or the people around me take real steps to be more careful with our data.

I believe a significant part of this issue lies in the fact that people are not truly aware of what happens to our data. While oil is tangible and comes with a clear price tag, data often feels abstract and intangible to many people. Yes, our data is being sold, and everyone knows that this is likely not in our best interest, but what does this actually mean? For me, at least, it’s not alarming enough to change the way I use the internet.

What Does It Mean That Our Data Is Being Sold?

Companies use your data to display personalized ads. This might seem harmless, but it can lead to manipulations of purchasing behaviour that may have larger consequences than you initially realize. Imagine searching on your Amazon account for self-help books about mental health issues, gambling addiction, and debt. Amazon sells your search history, and while the purchase data is sold without identifiable information, it’s still linked to the same account. So, while an external party might not directly know who you are, an organization like your credit card company could buy this data and match the transaction totals and dates. Now, your credit card company knows you might have mental health issues, gamble, and are likely concerned about debt.

Now imagine if a health insurance provider did this. They could gain access to information that helps them cut costs, for example, by cancelling insurance policies for high-risk customers even before clear health issues are reported. After all, corporations aim to maximize profits. This means, on one hand, extracting money from consumers by getting them addicted to products through targeted ads, and on the other, reducing costs by excluding risky customers.

The fact that I use Google Maps without much resistance is emblematic of a broader trend. We accept these hidden costs of “free” services because the immediate benefits seem more appealing than the potential risks. The convenience of technology outweighs abstract concerns about privacy. But how long can we maintain this before the consequences become tangible?

Perhaps it’s time to reconsider the phrase ignorance is bliss. Because as comfortable as it may seem to turn a blind eye, the reality of data being sold is one we can no longer ignore.

Your blog really raises an important point about how the convenience of digital services often blinds us to the risks of data misuse. I also think that many people, including myself, overlook these concerns because the benefits are more prominent than the risks. However, your examples about how data could impact credit or insurance decisions really made me think! We should all pay closer attention to this subject.

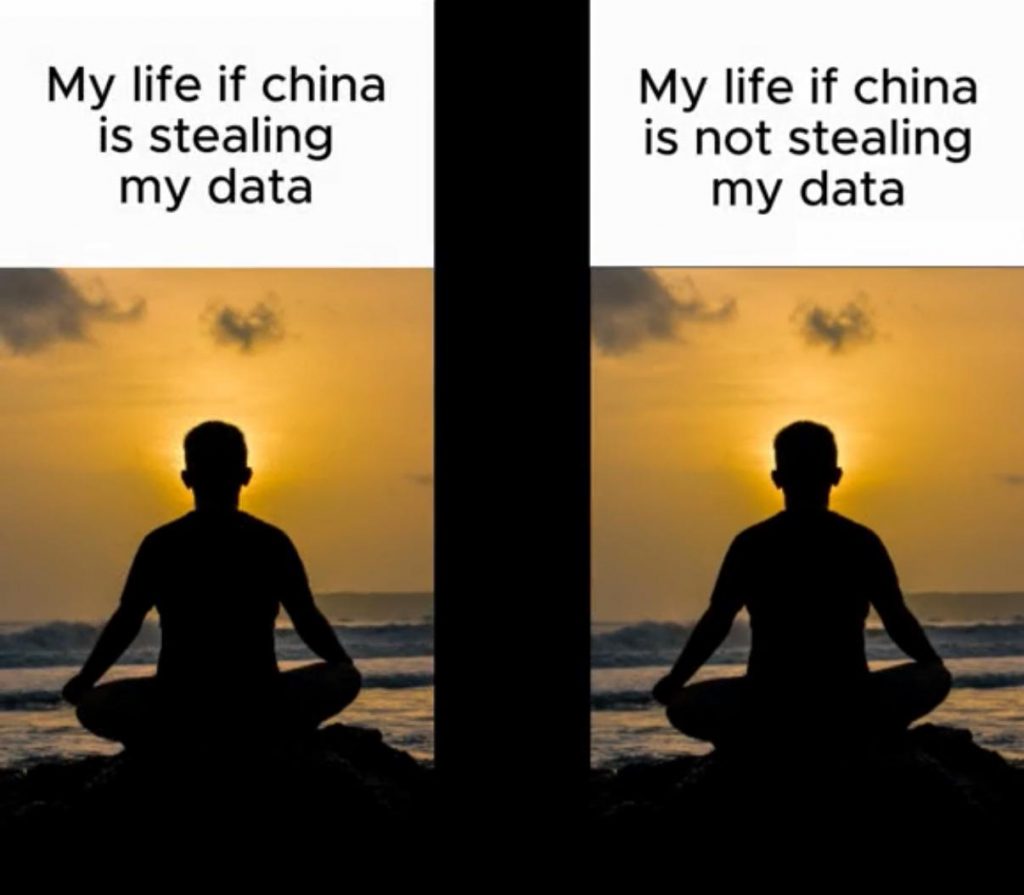

I think your blog brings up a lot of fascinating points that are especially important to think about now. I remember when the TikTok ban in the United States was going on, people were posting how they were willing to even send their data to China themselves or people joked about making their RedNote username their social security number. Even though they were joking, it really brought to light how few people know what it means for companies to have access to so much of our lives through our ignorance of what giving them our data means. Even I barely know what it means when I let websites have cookies since I, like most, don’t read the terms and conditions and just hit accept so the pop-up goes away. Whether or not I’ll stop doing that is something that I’ve been pondering over, but it is unfortunately easier to not and just let these major companies have my data.