It is a truth universally acknowledged that people create a certain persona on online platforms, such as social media. How we love to display ideal versions of ourselves. Share life’s highlights, and keep the darker parts in the shadow. Even ugly truths will be twisted into an appealing, curated post to stand out and attract the viewer’s gaze. There are, of course, exemptions, but to reveal every part of you to thousands of known and unknown people demands enormous courage. Moreover, there is the question of why you would want to share such intimate moments.

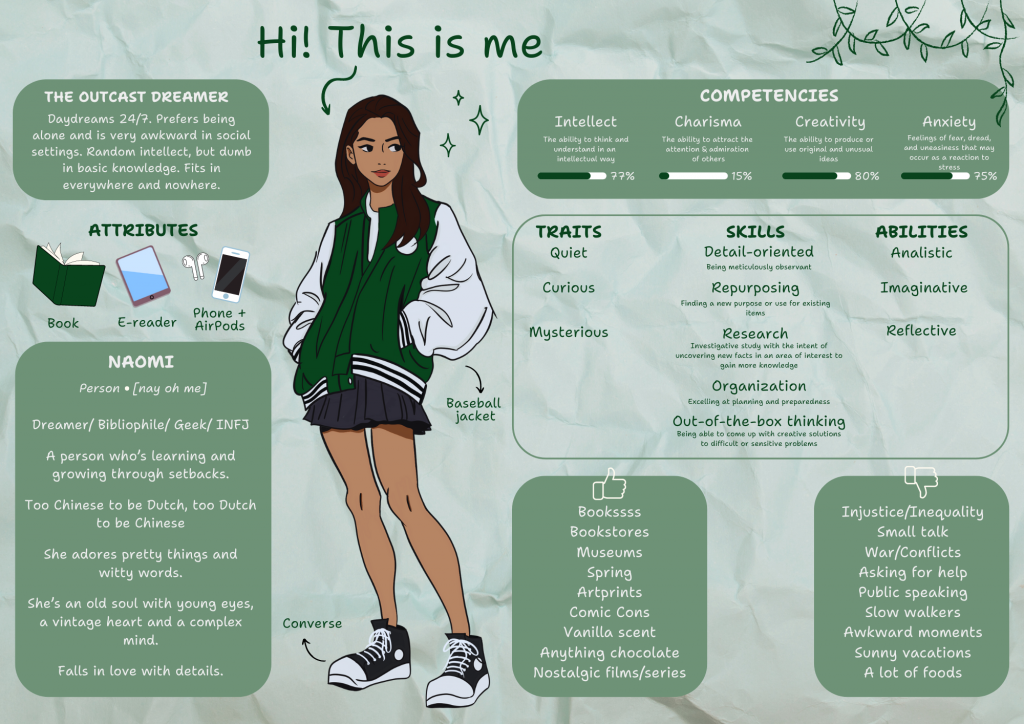

Over the years, I have created various social media accounts and profiles for role-playing games. I love building a character, an avatar of whom I can control every aspect, from her looks to her personality, and sometimes even her dialogue. I have always loved makeover games, whether online or with my family. It gave me a sense of control over how people see and think about me. I am an Asian-looking girl with a Western soul. My looks have been talking for me, instead of my own voice. Especially in multicultural environments, people take me for granted. Talking in English, keeping their dogs at bay, they consciously or unconsciously put me in a category. Particularly in my infant years, I was considered a rarity, a form of awe and entertainment.

With two white parents, where the heck did I come from? My parents would laugh and respond: “We just love eating Chinese food”.

I love them for that, for how they taught me not to care about my looks or the judgment of others. That is not to say that I secretly longed to look a bit more like them. Bigger eyes, or an upturned nose, some lighter skin and jeans for clothes.

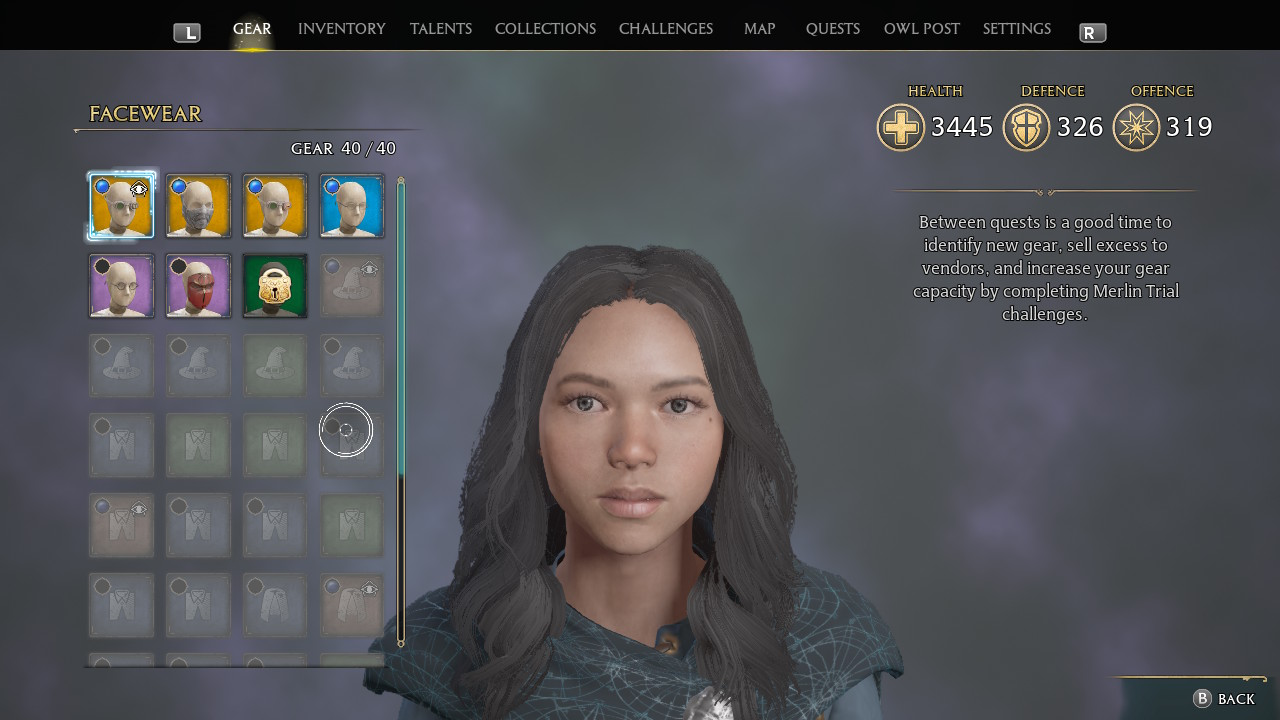

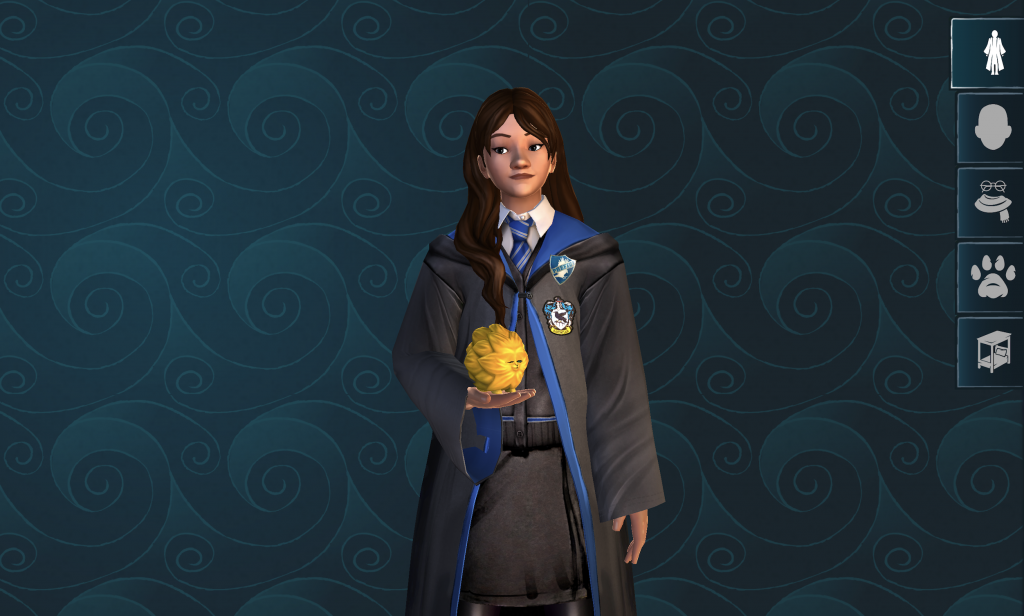

Enter the digital world, where you can filter and correct your way through it. Alas, my soul could stay intact! I found it interesting that games like Hogwarts Legacy, The Sims, and Episode can not accurately capture my looks. I would not want to create a persona that is stereotypically white with blond hair. I gave my avatar a tanned skin colour, dark brown to black hair, and smaller eyes than the default setting. Still, it did not look ‘Chinese’. Somehow, it still felt Western. I experimented to see to what extent it would take me for the game to create a Chinese-looking character. And guess what, it was not until the skin colour was close to white or yellow, with the blackest hair and smallest eyes, that it presented this ‘Chinese’ vibe. Maybe it is just me, maybe it was the childhood shows like Bumba or Ni Hao Kai Lan, that shaped my perception of what Chinese people look like.

I find myself in a complex identity crisis when the media features news of Asia. Or when I read books by Asian-Americans that try to diversify stories.

I feel these strange connections towards a folk that I do not belong to. Towards a culture I am fascinated by, but am no part of. Not by heart or by soul at least.

Here, I want to point out how digital media is significantly shaping the perception of our cultural worldviews. Recent studies are rethinking third spaces in the digital era. A third space, according to Homi K. Bhabha, refers to a “site of cultural hybridity, where multiple cultures intersect and thus form new identities“.1 While Bhabha explained this concept through a colonial framework, this blog will focus on a more contemporary approach. This third space can thus be both a physical and an imagined space, and now with social networking, even a digital space.2 The digital media has significantly contributed to our access to cultures that are not our own. It has allowed these cultures to see and interact with each other.3 Despite its contribution to broadening our knowledge, it has also created confusion, which can develop into misunderstandings and misinformation.

We always talk from our (Western) perspective: Instagram, Facebook, Netflix, Hollywood, and Silicon Valley. But we often forget that these forms of media are not as common in Asia. They use WeChat and other platforms that I do not want to risk naming without having the expertise.4 Those curious will probably go to a search engine and look for ‘social media alternatives’. Why is it that those are the alternatives?

How can we consider any digital media as a ‘third space’ while always carrying our own cultural perspectives and knowledge?

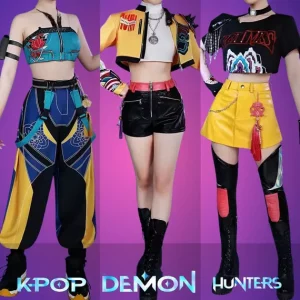

My final case study is the recent Netflix hit Kpop Demon Hunters. I am a big fan of the movie, with its stunning visuals and catchy songs. While they succeeded in making an Asian-American movie without emphasising Asian culture (in my opinion, it instead focused on deeper themes like friendship, found family, and self-acceptance), it quickly fell into the hands of capitalism, which turned it into an industry of costumes and food.

This may seem harmless, and not everyone is consciously aware of the decontextualisation it proposes. After the film’s release, it was met with criticism about its Chinese references.5 From a Western point of view, I get the confusion. Without having the right knowledge, I find it difficult to separate the various Asian cultural elements and traditions. However, I can understand that this is harmful to those who do belong to these cultures. With Halloween coming up, I am afraid that many will dress up and spread the incorrect cultural appropriation.

Still, this leaves me in a complex ‘in-between’ space that can not be described as a third space even through a digital framework. Maybe I have not found it yet, maybe it still needs to be developed. In the meantime, I wriggle myself through my diasporic identity.

────── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──────

Resources

- Bhandari, Nagendra Bahadur. 2022. “Homi K. Bhabha’s Third Space Theory and Cultural Identity Today: A Critical Review”. Prithvi Academic Journal 5 (1):171-81. https://doi.org/10.3126/paj.v5i1.45049. ↩︎

- Raine, Sophie. “What Is Third Space?” Perlego Knowledge Base, August 5, 2024. https://www.perlego.com/knowledge/study-guides/what-is-third-space. ↩︎

- Edirisinghe, Chamari, Ryohei Nakatsu, Adrian Cheok, and Johannes Widodo. “Exploring the Concept of Third Space Within Networked Social Media.” In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 399–402, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24500-8_51. ↩︎

- Statista, “Most Popular Social Media in China Q3 2024,” February 26, 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/250546/leading-social-network-sites-in-china/?srsltid=AfmBOopX-m8KFEfUB3CaMjzxagD-nr066856NdaHKesi3aFqa7rVgKzl. ↩︎

- See: Bhandari, Nagendra Bahadur. 2022. “Homi K. Bhabha’s Third Space Theory and Cultural Identity Today: A Critical Review”. Prithvi Academic Journal 5 (1):171-81. https://doi.org/10.3126/paj.v5i1.45049.

Phillips, Maya. “The Overlooked Element to the ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ Phenomenon.” The New York Times, August 28, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/28/movies/kpop-demon-hunters-fandom.html.

Instagram. “은지eunji Kang (@Eunjiscos) • Instagram Photos and Videos,” n.d. https://www.instagram.com/p/DLbK5iNs-Fn/

Sophie-Ha. “A University Professor Sharply Criticizes Chinese Netizens Who Claim ‘Kpop Demon Hunters’ Used ‘Chinese Cultural References’”. Allkpop, June 25, 2025. https://www.allkpop.com/article/2025/06/a-university-professor-sharply-criticizes-chinese-netizens-who-claim-kpop-demon-hunters-used-chinese-cultural-references.

↩︎

Redkar, Surabhi. “The Best ≪I≫KPop Demon Hunters≪/I≫ Collabs and Merch to Check Out.” Prestige Online – HongKong, October 3, 2025. https://www.prestigeonline.com/hk/lifestyle/culture-plus-entertainment/the-best-kpop-demon-hunters-collabs-merch/.

Recent Comments