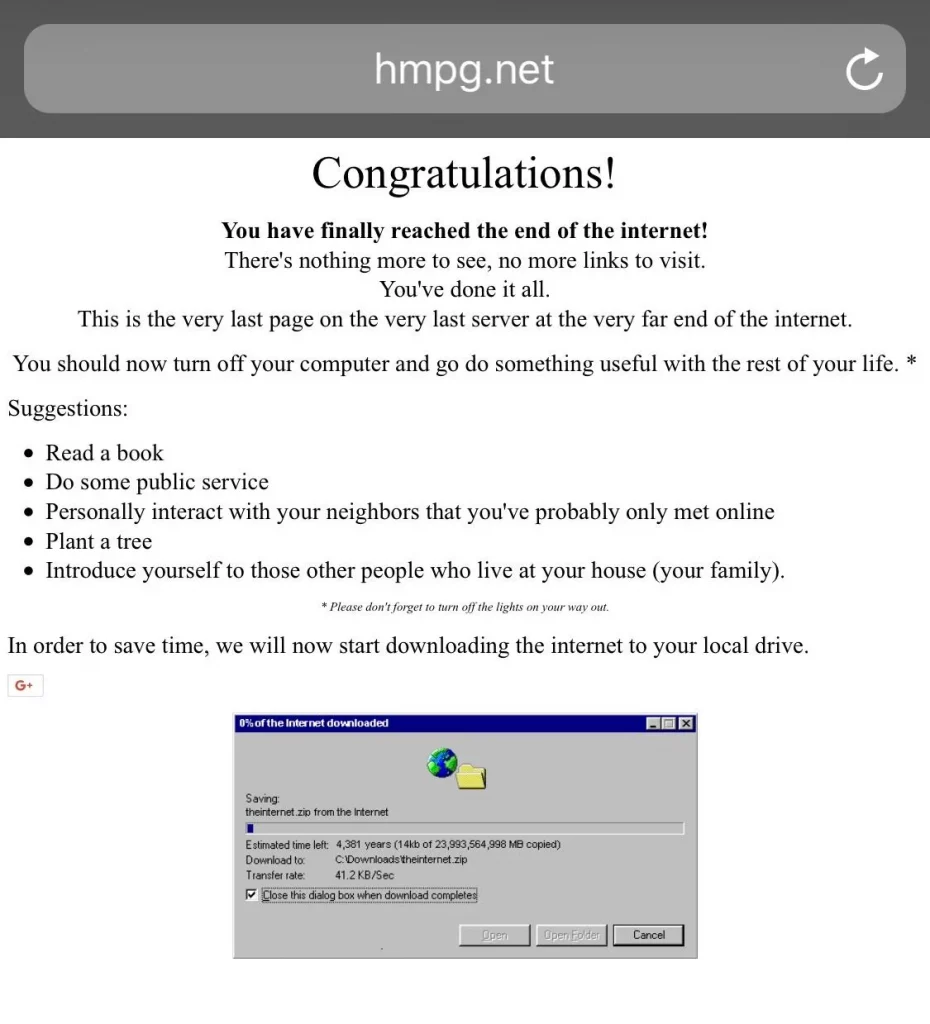

There was a time when the internet felt small enough to finish. Somewhere between early forums, webpages, and endless click-through rabbit holes, you could stumble onto a site that simply said to you:

It was a joke, obviously. But back then, it didn’t feel impossible. The web was vast, but it still seemed like a library you might eventually wander through cover to cover. The prank worked because it landed in that space of belief, it gave you a pause, a quick wait, what if? moment before you laughed and clicked away.

That pause is what sticks with me. It was a reminder that the internet wasn’t a natural landscape, but a construction. Someone built this page, gave it authority by making it look final, and for a second you bought it. It wasn’t about content, it was about the frame, the way the system made you stop and think about where you were. (yes, the buffering meant a lot to me) 🙂

Google was building something very different at the same time. In 1998, Sergey Brin and Larry Page were busy describing their new search engine, a tool that would “provide high quality search results over a rapidly growing World Wide Web.”1 Their PageRank algorithm was simple and elegant: pages would be ranked not just on keywords, but on the “number and importance of other pages that point to them.”2

The brilliance was speed. Type a query, and in less than a second you had an answer. The pause was gone. Behind the scenes, an entire infrastructure of crawling, filtering, and ad-bidding was happening, but on the surface it looked effortless. Knowledge wasn’t presented as constructed, it was presented as given.

That’s the sleight of hand. Where the “last page” prank exaggerated the frame to make you notice, Google perfected the opposite: it hid the frame so completely that you forgot it was there. Page one of results became the world. Has anyone in our generation ever gone past the first page of Google’s search results?

Decades earlier, H.G. Wells was worried about a similar problem, though the technology was different. In 1937, in a lecture later collected in World Brain3, he argued that the modern world suffered not from a lack of information, but from disorganization. Too many fragments, too little reflection.

For Wells, the solution was a new kind of encyclopedia: constantly updated, carefully organized, designed to slow things down and digest knowledge before spreading it. Reflection, he believed, had to be built into the system.

That puts the three moments into perspective. The early internet, where the “last page” prank gave you a pause and reminded you of the seams. Google, which engineered those seams out of view and made the pause disappear. And Wells, who insisted that a pause was not a nuisance but a safeguard.

So what does that mean for how we actually find knowledge online today? It means the responsibility for pausing has shifted. The systems won’t stop us. The prank pages are gone, and search engines have no interest in slowing us down. Everything is designed for smoothness, immediacy, efficiency.

Staying critical means resisting that smoothness. It means treating the first result as a suggestion, not an answer. It means following citations, checking dates, asking why this came up first and what might be missing. Small habits, but they add friction back into a system that works hard to erase it.

The “last page of the internet” was a joke, but it carried a lesson. The internet will always look like it has an edge, a boundary, a place where the answers run out. That’s part of the illusion. Google offers the same trick, just in a subtler form: page one as the end of the search. Wells would remind us that neither is the end, that knowledge only becomes meaningful when it’s slowed down, digested, thought through.

There is no last page. There never was. But the pause it created, that moment of recognition that you were inside a system, still matters. If the web won’t build it in anymore, then it’s on us to remember that it exists. And its in that space that we will be able to remember not to believe everything we see on the internet.

- Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, Stanford University, 1998.

http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html ↩︎ - Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, Stanford University, 1998

http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html ↩︎ - H.G. Wells, World Brain, Methuen & Co., 1938 ↩︎

“It means the responsibility for pausing has shifted.” This really made me think, and also about the fact that I don’t think I have ever gone beyond the first page of a google search. I just searched up a random thing “cats” on google to see how far I could scroll, to find that there were at least 10 links, plus AI , wikipedia, and suggested questions before reaching the bottom.

I think what we learn in university about vetting sources, and making sure we are using reliable arguments is very important, but I do find I draw a harsh line between doing that for uni work, and completely going off of the first result or even AI overview when its just for my life. This seriously makes me recognize that in myself and see how I should be more wary and take responsibility for my searching and ‘pauses’ on the internet.

It was a bit confronting when you asked the question if people of our generation have ever scrolled past the first page of google. It made me think and although I think, in my lifetime, I have, it sure is long ago. That shows exactly what you talked about, that nowadays everything on the internet has to be fast. Maybe it would be a good thing if I would take a ‘pause’ from the internet sometimes.