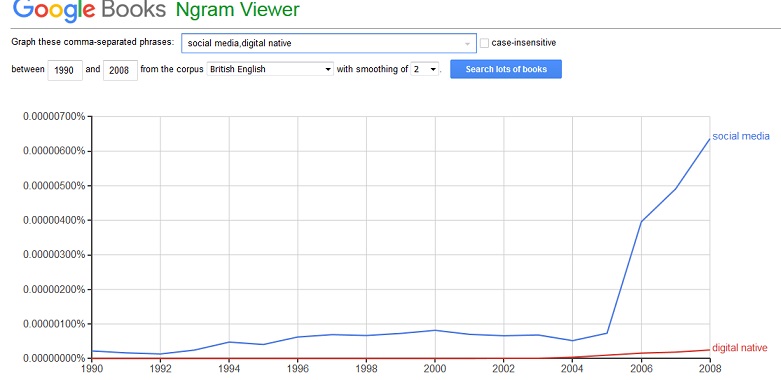

There are a couple of everyday, digital media terms that really bother me: ‘digital natives’, because it presupposes you can classify people into generations and dismiss alternative life experiences based on year of birth; and ‘social media’ because the term ‘social’ implies friendly interactions, not just neutral organisation of society, whilst it really hides negative behaviours such as bullying, hate speech, and promotion of unsocial behaviour in everyday life. According to Google Ngrams, at the end of 2008, ‘digital native’ was not that popular, but along with ubiquitous ‘social media’, it still raises itself in conversations.

It’s time, however, for more neutral terms like ‘networking media’ instead of ‘social media’. (Unless society is going to promote using the term ‘unsocial media’.) That would leave the term ‘social’ for physical interactions between people that promote mutually beneficial connections, and not give use of these communication tools a more positive image than they deserve.

My experience of digital media has changed through the years and also changes depending on my environment. When I emigrated to Canada I already knew that I wanted to get rid of my TV. And that was perfectly possible when the BBC was not available, and the choice was from dozens of similar, advertisement-heavy North American TV stations. It was also possible because I could go hiking in the Rocky Mountains rather than needing to escape into the steampunk/deserted landscapes of a computer game like Myst.

Now back in the Dutch Randstad, I’ve renewed my compulsive viewing of the BBC on my phone and on TV. Why the BBC and why only the BBC? For one it has no pay wall, and unlike most newspapers does not pepper me with requests to support their journalism, and mostly I’ve grown up to trust the BBC as providing unbiased reporting and well-crafted, advertisement-free entertainment. But still I browse far too often to the BBC pages – it’s a kind of comfort blanket. And perhaps that is what a lot of the addictive online behaviour is – something to fill in time rather than engaging with the physical world that is increasingly urbanized.

My daily experience of ‘social’ media I limit to e-mail and Watsapp. These tools allow me to tailor my messages per person and group. Facebooking promises that you can contact all your friends with a one-size-fits-all message, say, about your depression, exotic holiday snaps, or your views on dieting, and you don’t need to worry about how an individual receives your message. But that one message will affect your friends and family and perhaps hundreds of Facebook friends in different ways that are impossible to control on such large scales. It hijacks other people along on your mood swings – and how can they properly react if they are not in the same room as you? Perhaps that’s why some Facebook users just post pictures of cute cats. Facebook then soon becomes repetitive, or gives ‘Too Much Information’ or becomes a means for advertisers to know you better than yourself. Humans developed communication for smaller social groups – public speaking came much later, and not everyone is comfortable talking in front of large crowds.

So my mantra for daily use of digital media is to be conscious of what I put online, and reduce my screen time by a focused use of the internet. And spend as much time as possible in nature.

Resources

Wikipedia: wikipedia.org

Google Ngrams: https://books.google.com/ngrams

BBC: https://www.bbc.com/

Recent Comments