Fragmentation and risk taking

Maffessoli observes that the idea of the ‘individual’ is in retreat and is suffering fragmentation; and that the individual Self seeks a more profound way of being and is returning to the support of larger groups – this Maffessoli describes as tribalism (italics my emphasis):

“The heir of the culture of reason, of a history we can control and of a consensual social bond is a culture of instinct where people want to face up to destiny. The former has a predictable plan and talks of a career, whether it be in economic or educational terms, while the latter is all about chance, risks and adventure.” (740)

Maffessoli acknowledges that these feelings of wanting to live more instinctively are not new, and the return to a wilder more passionate way of living – now seen in the rise of Social Media tribes – could also be seen in the age called Romanticism:

In fact, with the help of technology, we see a return of the so-called daemon of Socrates, which we can also observe in Romanticism. This concept emphasizes the strength of organic growth as the instinctive foundation of the functioning of any living being. (740)

Maffessoli’s definition of the tribe

Maffessoli gives three ‘great characteristics’ of tribalism as well as talking about people wanting to return to risk taking, the wild side, wanting to live more passionately, and stay young and vitally interested in life:

“They are: the importance of the territory in which the tribe finds itself; the sharing of common tastes; and the return of the eternal child. All three are paradigmatic of the feeling of belonging which is both the cause and effect of tribalism.” (742)

The original tribe: family

It’s noticeable in Maffessoli’s article that no mention is made of the most basic tribal unit, i.e. the family, except possibly in his dismissal of ‘clannish communities’. Because of easy, long-distance movements of individuals away from family and local communities traditional ways of being, language, and culture are fragmented. Like Star Trek, people ‘teleport’ themselves into new worlds suddenly without sufficient time for both traveller and host to adjust. Social Media can fill the gap caused by lost connections between family members. Online groups offer support and education in bringing new communities together. Chat rooms and online role playing platforms can offer friendships, new worlds and adventure. (In many cases risk is done in anonymity). But I think it’s often underestimated how difficult it is to integrate long-term into a new culture and break from older family networks, and overestimate how much Social Media, Skype and email can replace a real handshake or a real hug.

Social Media as escape valve

In ‘Tales from Facebook’, Daniel Miller describes an example of how one subject’s Facebook experience fuses with her experiences of real-life community. Alana lives in close proximity to her family and extended family in Santa Ana, Trinidad. This real village has two sides ‘a romantic idyll of community’ with a ‘feeling of common identity, of solidarity and common care’ (18), but it is also a real village with ‘all its troubles and potential claustrophobia’. Alana does not express herself as an individual, but understands herself as part of ‘the networks she lives within’. And because of being aware of how important her real-world networks are she was reluctant to join Facebook. However, she was persuaded by her cousin to join, and now loves it, using it mostly to keep in touch with university friends and on top of her studies. She goes to sleep at 8 pm and gets up to chat on Facebook from midnight to 3 am. Alana is aware of Facebooks’ negative side, which encourages an invasion of privacy, but on balance she finds Facebook calmer than real life, and replaces the more static TV watching she used to do with her family and friends. For Alana the internet is an important part of her life. Being online helps her keep a good balance with her more intense, face-to-face community life, and she is thriving.

Tribes in mind

Online tribalism is just another label for a human need to bond, make friendships, and share similar passions and interests. These are feelings that are widely and also historically present in humans – they are not new. The reach towards kinship of some kind is always present. New technology in the form of Social Media is one tool that individuals can use to achieve a connection, but those connections are still mediated through a computer screen.

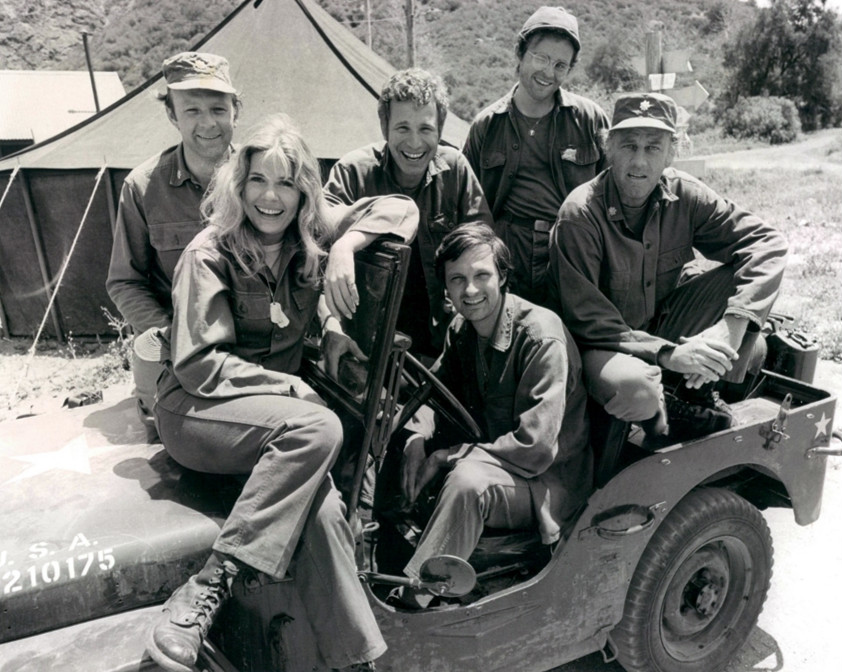

Can you be part of a tribe that doesn’t know you’re there? Do you lose your individuality once you choose to join ‘a tribe’? The BBC is my one-sided online tribe, a link to my British roots, but I’m just another IP address to the BBC. If I think about examples of tribe behaviour in TV film and books, I think in terms of the medical crew of BJ, Hawkeye, Hot Lips, and Radar in 1970s TV cult series M*A*S*H, or Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel, ‘Station Eleven’, where a travelling band of Shakespeare players and musicians travel through a dangerous post-apocalyptic world.

(https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/MAS*H_(televisieserie)]

Tribe under times of duress

My idea of tribe would be a grouping of individuals who provide friendship and have a protective function; a nomadic feel of exploring new worlds, and a shared focus of intellectual interest and purpose. There are online tribes who can meet those criteria, but I don’t think they can operate in a vacuum. Most people need to be attached to real-world tribes with meaningful connections at the same time. The question is how to get the right balance online/real, leaving sufficient energy and time to be and act in the real world.

References

Michel Maffesoli, ‘From Society to Tribal Communities’ in: The Sociological Review (2016) pp. 739 – 747.

Daniel Miller, ‘Ch. 2 Community’ in: Tales from Facebook (Polity, 2011) pp. 16 – 27.

Recent Comments