Back in early 2013, some friends and I were introduced to an upcoming ‘indie’ (independently developed) game called Cube World. It promised an open, procedurally generated world in a voxel-based art style full of fantastical locations, creatures, and things to do. Hang gliding, sailing, mountable pets, and good old running around were the main methods of getting from A to B in this grand world full of castles, dungeons, forests, volcanoes, and other destinations. It was undoubtedly a project with grand aspirations, and that is likely where the problems began.

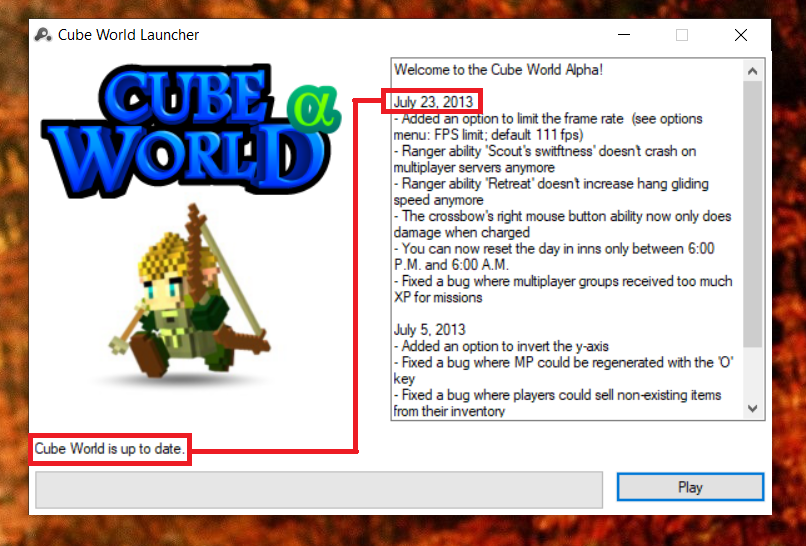

One thing that is particularly noteworthy when it comes to the development of this game, is that it was programmed by one person, a German man called Wolfram von Funck, known online under his alias ‘Wollay’. The art was also done by a single person, namely his wife Sarah von Funck, known as ‘Pixxie’. This, in combination with the game’s voxel nature, inevitably lead to comparisons being drawn between Cube World and the massively popular Minecraft, which was initially also an indie project programmed by one person. The Cube World alpha version was made purchasable to the public for a very limited time in July 2013, by which time these comparisons had caused the upcoming game’s popularity to skyrocket. My friends and I bought the game at this time, and had a lot of fun with it. Eventually however, as virtually every player of the game did, we ran out of things to do in it, and our interest in it swiftly dwindled. This is where the ‘public failure’ part of this topic comes into view.

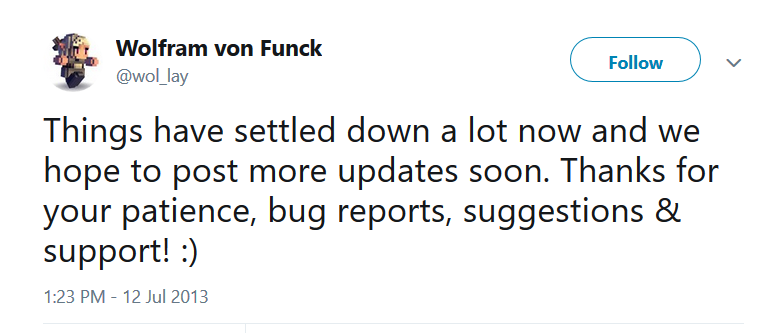

Whereas Minecraft had swiftly expanded its development team following its discovery by the public, and been able to pump out regular updates to sustain the community’s interest, Cube World remained a two-person effort. This was most likely the case due to the very personal nature of the project for Wolfram von Funck. Von Funck promised to update the game sometime soon, and started releasing screenshots and videos of his progress towards doing so. The problem is that this update simply never came. It is of course understandable that such a thing would take a considerable amount of time when the team exists solely out of one programmer and one artist, but the public still had high hopes. The community’s goodwill towards the developers started to turn sour as months without an update turned into years. This only got worse over time, with people claiming that the von Funcks had simply ‘taken the money and ran’ and warning people that the game would never be updated any time Wolfram von Funck publicly showed his progress. The entire project was now deemed ‘vaporware’, meaning that it was seen as empty advertising and promises with no actual product to back it up, a stance that was strengthened by the von Funcks’ decision to rescind the game’s purchasability shortly after its initial release.

However, despite this public backlash and the perceived failure of the game in the public eye, the von Funcks did in fact continue to develop it. In early September 2019, more than six years after Cube World’s initial release and last update, a major update was finally announced. The update is due to be released on the 30th of September 2019, with owners of the alpha version being able to play it a week early, starting on the 23rd. The game will also become purchasable again from this point onward, thus marking a great personal success for its development team, as they appear to finally be confident enough in their project to truly release it this time. The community’s interest in the game has certainly been rekindled following this announcement, but whether it will ultimately suffer from its history or be a tremendous success in its resurrection, remains to be seen. Either way, the development history of this game is a fascinating example of the disconnect that can exist between the idea of a project’s success in the mind of the developers and the public, the latter seemingly demanding constant attention at the risk of public disappointment, disinterest, and sometimes even anger.

Hey Connor,

I really like your use of language in the blog. The whole text flows nicely and the choice of words is very varied.

I appreciate that you explained the term “vaporware”. I feel like expressions such as “procedurally generated” and “voxel” could also lead to some questions as they’re not really used in everyday language and as such could use some further explanation.

I think I remember this game from back in the day and there was quite a bit of hype around it, right?

Cute that it’s actually a project where he wrote the code and his wife did all the artistic elements of the game.

Personally, I would love if the developers had some success with this game, even though they somewhat missed their chance of jumping on the pixel-survival-openworld-game hype train that came with Notch’s creation of Minecraft.

Hey Leon,

Thanks! I’m glad you liked this blog post. On the topic of technical terms such as the ones you mentioned, I think you are entirely correct. I should have included a short description, but forgot to think of that. Going forward, I will try to be more clear!

And yes, there was a lot of hype around Cube World, which was probably part of the problem. People have an unfortunate tendency to get too ‘hyped’ for things they’re interested in, to the point where the actual product simply cannot live up to it.