Even though we surround ourselves with digital content every day, the idea of digital art being a part of media art can be quite peculiar to many of us. Media art consists of video art, digital art, as well as documentation of performances. It is something non-physical, and intangible, and can take so many different forms. The task of treating media art the same way as traditional art is not easy. How does ownership work when it comes to this form of art? How to put a value on something made on it? Who has the right to distribute the work? How to curate media art?

To answer some of these questions I want to introduce LIMA which is a platform taking care of media art. They preserve it by working with artistic institutions and store collections of museums such as De Appel or organizations like Time Based Arts. Even though those works are stored digitally they can still be owned by a museum or private collectors. LIMA also distributes those artworks, which means that they take care of renting them for exhibitions and festivals (both from artists and museums). Other things they do are research and doing projects based on their collection. Since media art is relatively new and is still developing, there are not many organizations devoted to tasks done by LIMA. The platform is constantly evolving and emphasizes a variety of artists they work with, from emerging makers to established pioneers.

LIMA works as a digital platform and serves as an accessible source of information about digital and media art. By browsing their website the idea of media art can become less abstract. You can see what forms such art can take.

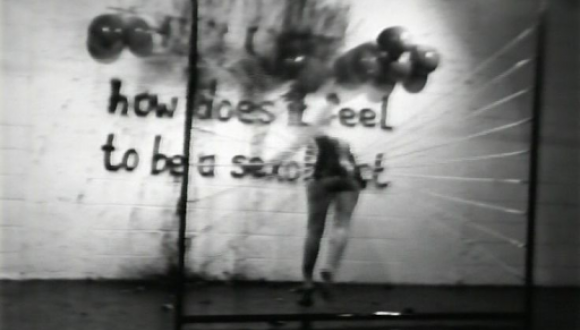

Sex Object, Lydia Schouten, 1979, LIMA Collection, 18’41”.

Now moving away from LIMA, I would like to reflect on the intangibility of media art. It is interesting to reflect on how artworks made digitally can fall under the same umbrella as for instance documentation of happenings. The first ones exist in a digital space, and could even be a part of virtual reality, while performances or happenings are time-based and belong to the physical space. Through media such as video, things related to reality are deprived of their tangibility and become blended into the digital space. Digital collections become a means of preserving both digital heritage as well as real-life events.

Nowadays with such a huge presence of digital media in both daily lives and art the things related to non-digital get intertwined with those belonging to the digital. Organizations such as LIMA help to contextualize media art as well as put value on it, giving answers about the importance of digital in the art world.

Sources

Thank you for writing this blogpost! I had not heard about LIMA before, so it was interesting getting to know more about it! You write: “Digital collections become a means of preserving both digital heritage as well as real-life events”, which is most certainly great, but it also made me wonder: what preserves the website LIMA? I remember a Dutch author (Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer) who once wrote he is happy he printed all his books, so his writing will still be available when Word crashes. Would it be an idea to convert the online digital art to an offline piece by trying to print or 3d visualize them? Or is the fact that the online world is a rapidly changing environment part of the art?

Hi Mette, to dive further into this train of thought; I think that the internet (or the digital) is actually a really helpful tool when it comes to preserving, as everything on the internet is archived already. As a photographer, I have had to deal with the pitfalls of the preservation of an offline archive (water damage made most of my negatives completly moldy and damaged). Plus, these digital projects are something that can’t really be replicated, right? (although I like the proposal of 3D printing). To add on the post by Olga, I think the concept of conserving digital heritage is fascinating because it allows for less canonisation, reduced institutionalization, and greater public accessibility.