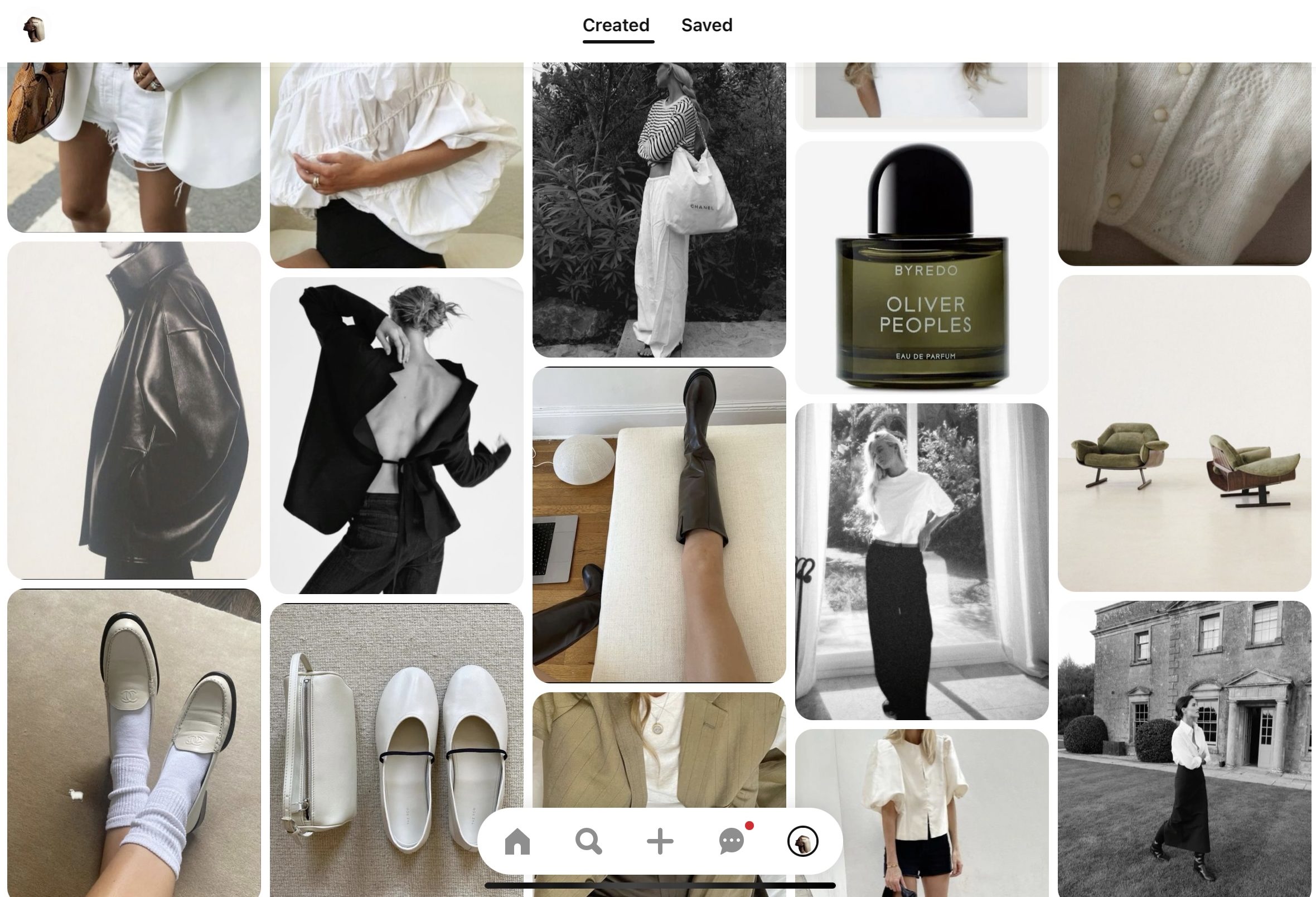

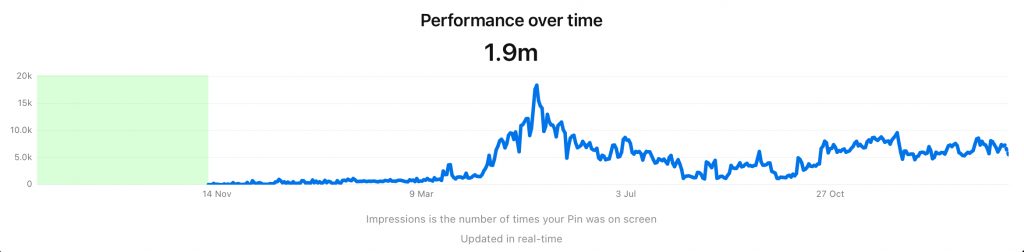

I spent hours curating my Pinterest boards—perfecting the balance between “clean girl” minimalism and “quiet luxury” refinement. At one point, I racked up over a million monthly viewers, all drawn in by an algorithm that rewarded aesthetic perfection. But lately, I’ve noticed something: the same trends I meticulously followed are now being mocked. The “clean girl” is called basic, “quiet luxury” is oversaturated, and every other aesthetic cycle is discarded just as quickly as it was adopted.

This isn’t just trend fatigue—it’s the collapse of subculture culture as we know it. Digital media, which once gave aesthetics their power, has also made them disposable.

From Subcultures to Stereotypes

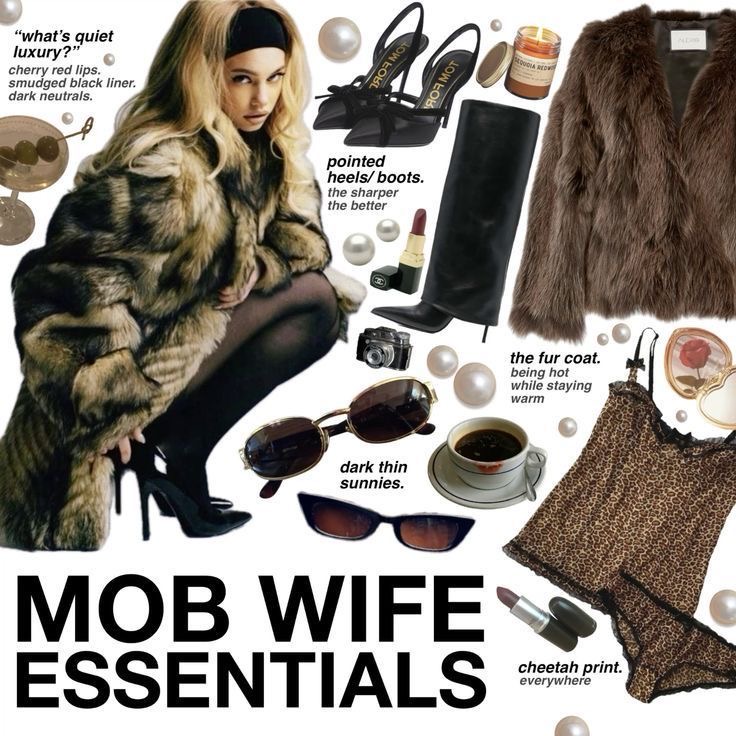

We categorise people instantly, often based on something as insignificant visual cues. See sheer pink nails and a sleek-back bun. “Clean girl.” A red lip and fur coat? “Mob wife.” It’s not just about aesthetics—it’s about assigning a fully realised identity, a set of values, even a lifestyle, to visual markers.

This is the logic of digital media. Platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Pinterest thrive on recognisable, repeatable patterns. A few defining traits become the shorthand for an entire category, making trends easy to package, consume, and discard.

Aesthetic Homogenisation

Ted Striphas’ concept of algorithmic culture explains how digital platforms dictate cultural production. Algorithms don’t just show us what we like—they shape what we like. When an aesthetic takes off, the algorithm amplifies it, pushing it into the mainstream at warp speed. The result? A visual monoculture where everyone dresses the same and decorates their home the same.

As Algorithmic Culture suggests, we aren’t simply choosing aesthetics — algorithms are choosing for us. Trends are amplified based on what performs well, not necessarily what holds meaning. The result is a feedback loop where aesthetics feel universal, but also strangely empty. The more we see them, the more they lose their appeal.

At one point, “clean girl” symbolised minimalism and self-care, but its mass adoption turned it into a cliché. “Quiet luxury” had an air of exclusivity until it was reduced to a Zara dupe of a Loro Piana blazer. Once an aesthetic is too accessible, it stops feeling aspirational. The algorithm moves on, and so do we.

Cycle of Trend Consumption

The problem with algorithm-driven aesthetics is that they rely on constant novelty. Digital media has turned aesthetics into empty signifiers—stripped of their original meaning and reduced to a collection of items on a mood board. A clear example is the downfall of “that girl,” the wellness-obsessed productivity it girl. Initially praised for promoting self-discipline, she was quickly criticised for being unrealistic and privileged. Every aesthetic follows this cycle: rise, peak, backlash, irrelevance.

Historically, aesthetics were tied to subcultures—punk, goth, and grunge emerged from specific social contexts. They had deeper roots than just visual style. Now, aesthetics exist in isolation, detached from any real ideology. They come with no real barriers to entry and, crucially, no lasting identity. This is why trends burn out so fast. Aesthetics are no longer about belonging to a movement; they’re about maintaining an image. And when that image is too easily replicated, it becomes disposable.

What Comes Next?

As aesthetics burn out faster, people are growing disillusioned. We’re already seeing a shift from hyper-curated feeds to “low-effort” digital spaces through photo dumps, where authenticity (or at least, the illusion of it) is the new currency. The irony? Even “anti-aesthetic” movements get labelled—effortless dressing becomes “indie sleaze,” and rejecting trends altogether turns into “normcore.”

So, is there a way out? Maybe the solution is to stop treating aesthetics as identities. The real shift isn’t in aesthetics themselves, but in how we engage with them. If we stop mistaking aesthetics for identity, we might resist the urge to categorise people so rigidly. If digital media killed the “core,” perhaps we should let it die.

Recent Comments