Who was I before having a smartphone?

When I once asked my mother this question, she spent days searching through our house and eventually found boxes of old DVDs, tapes, and photographs – hardly surprising, given that I was born the early 2000s. Over the following days, I watched these recordings of myself together with other family members. It was a heartwarming yet slightly embarrassing experience to see my younger self watching cartoons, playing in the children’s pool, and laughing and jumping as if I were the happiest person in the whole world.

These early recordings of my life later became, in a sense, a regular show in our household. So that whenever guests came over, my parents would insist (or so it felt) that they watch at least a particular clip of me imitating a television weather forecaster. Their favorite part is that I was too little to repeat a full sentence so I could only manage the final two words, which were usually the name of a city. Each time the tape finished playing, my mother would proudly remark that I had “grown so much” since then. Rather than praising me simply for being able to speak, I only realise much later the hidden nostalgia of reminding herself of how much love and time had passed.

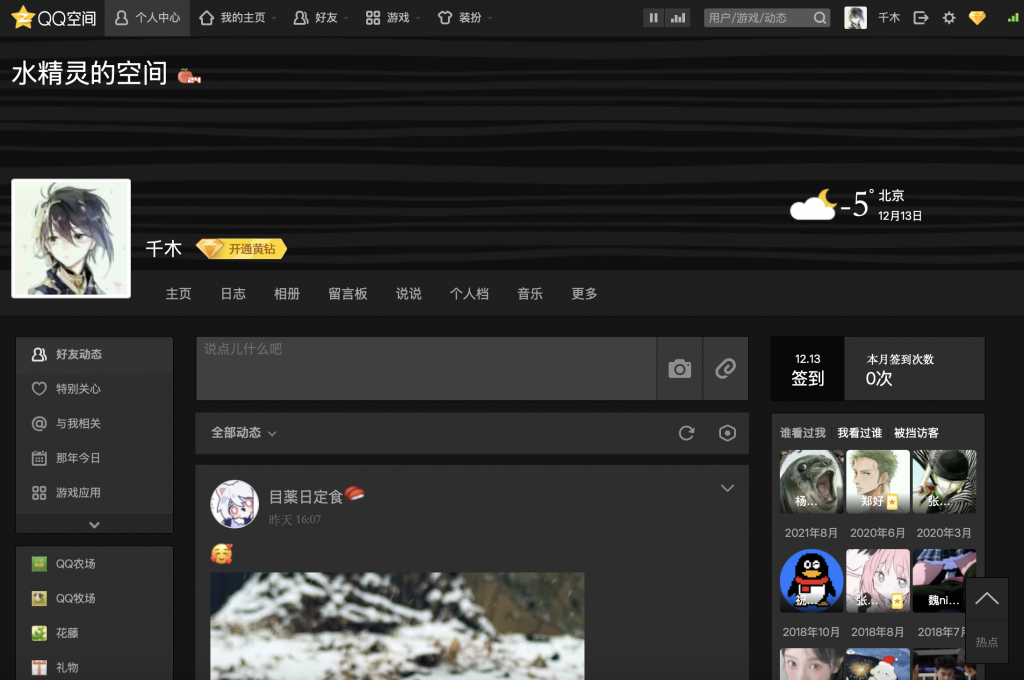

Ironically, I was less comfortable with photos as I grew. Arriving to my teenage years, I refused to watch old videos or appear in family photos unless I had to. With the first smartphone of my life, I spent hours on social media to hide myself behind words rather than images. At the time, I was obsessed with QQ space, where I posted and forwarded random content from my friends and strangers – somewhat similar to Twitter. I joined countless group chats and pretended to be an adult. When people asked how old I was, I would say I was eighteen, even though I was only twelve.

It was a slightly wild period of my life, one I can now only describe vaguely, because I later deleted every trace of myself from that space as looking back at it during high school felt too embarrassing. As a result, my digital memories between the ages of eleven and fifteen have become almost entirely blank. I cannot tell as I grew even older, whether I had spent more years feeling relieved about that decision, or more years regretting it. From my past experience, time seems to teach us only loss, while the question of how to live with endless longing remains unanswered.

The guardians of history

While bearing this pain of loss, I also notice how unceremoniously loss often occurs in everyday digital life. Have you ever tried to find a photograph of your parents from five years ago? Living alongside digital images and texts, we create them almost all the time and come to believe they are immortal – always waiting quietly in parts of the mysterious space (internet!).

However, a defining feature of our digital world is its ephemerality. Think of the pop culture, the radio plays music that was never designed to last but only for the moments. In this sense, little has changed between then and now – between radio music in the 1980s and scrolling through TikTok on my couch today. We create and lose simultaneously. Digital connectivity is speeding up almost everything to the extent that made us forget the values of keeping record when it comes so easily. For example, the smartphone was invented to better capture and share life’s moments, and we sure did but with even less last. This could also be transformed to a larger scale, the internet contains a vast number of inaccessible URLs, and we will never be able to retrieve their content – like my QQ space.

Then what could anchor our very existence beside the printed books, photo collection, handwritings and video tapes? And perhaps more importantly – does any of this matter? I’m sure the Internet wouldn’t mind, but for individuals – that is memories, and for humanity – that is history. To put in a bolder claim, that is us who want to hold something tight about our past. As we all once wondered who we are, the desire for the persistence of personal identity explains the necessity of retaining memories at different points according to John Locke. That is why deleted my space history is a bad idea as I could never know what I was in that specific setting. By contrast, I can always know how I learned to name cities on a weather forecast, thanks to my mother. So as for humanity, if we continue losing our digital trace, what would people know or not know about us thousands of years after. However, the question itself is far from new. We have faced it throughout history, and perhaps loss has always been part of what history is made of.

Down to the rabbit hole

That being said, I recognise that this may still be little more than a consoling way of speaking about what cannot be undone. As I am still trying to figure out a way forward with the past, so this blog can only serve as my obituary for my QQ space in a 2am morning. The impulse to keep chasing the past may seem foolish, yet I believe this insists forms an essential part of who I am. Perhaps this, too, is another way of preserving a personal history: by remembering constantly and forgetting only rarely. And before the weight of emotion overwhelms me, I hope my writing can carry part of it – and hold it, at least for a while.

Reference

Silicon Valley – The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World

We’re losing our digital history. Can the Internet Archive save it?

I enjoyed reading this a lot! Especially this part was very poetic: ” From my past experience, time seems to teach us only loss, while the question of how to live with endless longing remains unanswered.”

I understand what you’re saying but I am a true believer of saving as much photos, videos etc for the future. My phone storage is suffering, yes, but I somewhat enjoy the ‘cringey’ footage I took when I was younger, even if it may be a little too embarrassing to show on the tv to people visiting my house, hahaha. My advice: take more photos, you’ll thank yourself later (and if not, you can always delete it later): you don’t even have to post it! If you love the picture, you simply print it out, and if not; delete it!

What an interesting piece you’ve written, like a kind of self-reflection. Your blog got me thinking too: are there parts of my life that have completely faded because I didn’t record them, for example? It’s interesting that you start thinking so much about yourself after reading a blog. I notice that I always enjoy taking photos, but I usually do this of landscapes and not of people. I can remember the view perfectly, but afterwards I regret not taking a photo of the people who were there. Because your memories fade too, and that’s a real shame. Because it’s wonderful to imagine how we stood there, what everyone was expressing, what the vibe was like… These little things get forgotten, even though they’re actually the most important things. It doesn’t matter where you are, but who you’re with, and those are the memories you want to remember. This is a tip I can give, but I definitely need to apply it more often myself, because it’s also a kind of self-reflection that I need to do this more often.

wow thank you for sharing your unique digital experience. Im sure you are not alone a lot of us have had the same. Hyperfixating at 12 on another would you seem to discover for the first time and you can be anything you want in there. I really think that even though it can sometimes lead to dangerous situations its a part of our growing up experience and it shapes who we are. Im a really big photo taker esepcially in middle- school and high school and I really had this feeling too that having and taking thoses photos they would last forever I have not been able to delite them though but are scatered all over my digital devices theses days and I have no idea what do to with them. Its just a part of us.

Thank you for your post, it made me reflect a lot on my past memories and how digital technology led to the loss of most of them. It made me realize that while the album of my childhood are still carefully conserved in my mother’s home, other pictures or video of most of the experiences of my life are somewhere lost in my old phones. In this developing digital world, it is important to remind the value of tangible memories.