The responsibilities of users, platforms, and public authorities are rebalanced according to European values, placing citizens at the centre.

European Commission on The Digital Service Act (DSA)

European Union (EU) is quite a bizarre political entity as it is neither a nation nor an international organisation. The most recognised term, perhaps, is supranational organisation in which member states retain sovereignty yet transfer some of its authorities to the EU. Although it is not the goal of the article to elucidate what this post-WWII hybrid is, it is essential to first understand how EU developed from a mainly economically driven club of the six nations, to one of the most powerful socio-political unities around the global.

Post-War Europe: In Need of Stability

The notion that EU was first established purely for economic reasons is clearly naive. True, there is a need for Europe to recover from the economic destruction that the War has done to the countries in the region, particularly with financial aid from the United States (i.e., the Marshall Plan). Nonetheless, there is another crucial factor driving to initiation of the Council of Europe and the later European Coal & Steel Committee (ECSC), which is the desperation for security and the prevention of the future rise of nationalism within Europe.

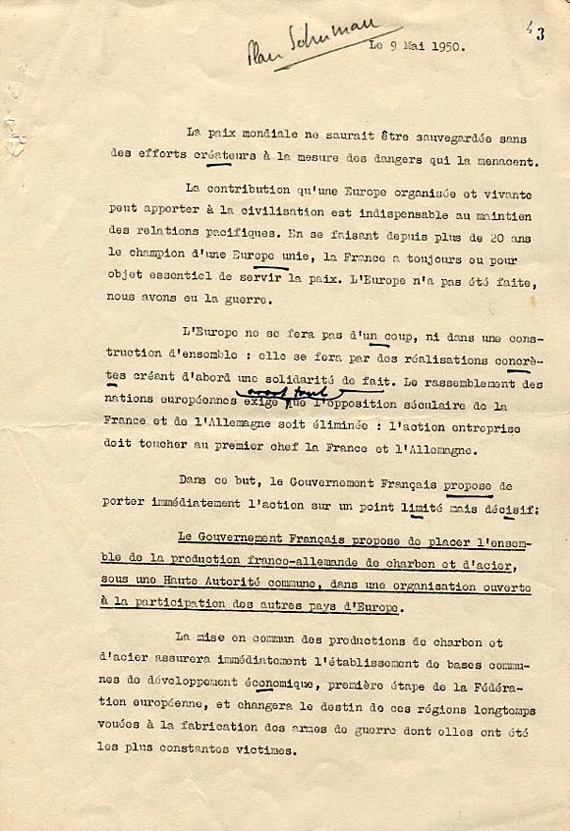

Advocates voiced their desire for a United States of Europe (États-Unis d’Europe) as early as 1860s, when the French writer and president of the Paris Peace Congress Victor Hugo expressed such vision at the Congress. This idea was later adopted by the British prime minister Winston Churchill in his famous speech delivered at the University of Zürich in the year of 1946, merely a year after the end of the war. A few years later, the French foreign minister Robert Schumann signed the landmark Schuman Declaration, the document which leads to the ECSC 2 years after the declaration.

The idea of Schuman is simple: once we can pool energy resources from the two European superpowers, Germany and France, a war is not “merely unthinkable, but materially impossible”. The establishment of the ECSC is viewed as a start of the following economic unification projects, for example the European Economic Council (EEC) and the Single European Act (SEA).

Technologies in the process of reunification

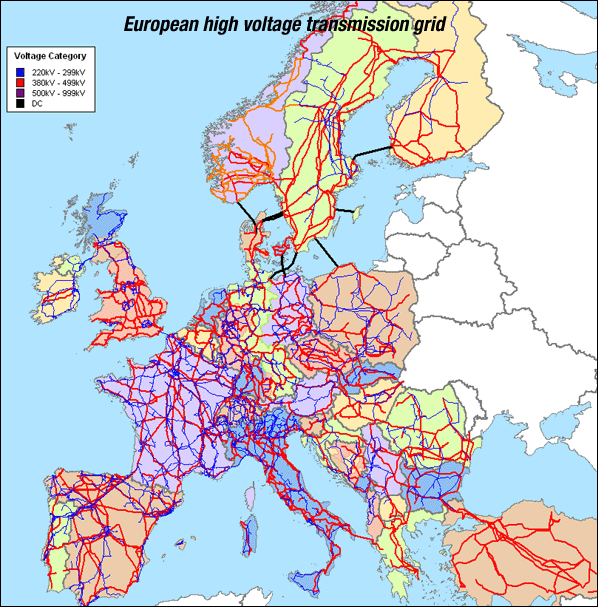

Historians and anthropologists of science and technology have illustrated a perfect picture of what really happened in the years of reunification in the EU from the standpoint of technology. For instance, Thomas Misa and Johan Schot in their paper Inventing Europe: Technology and the Hidden Integration of Europe has wittingly pointed out how technologies have shaped the topography of modern EU and the technologies per se are tools with political powers. Indeed, the EU first started with the ECSC, focusing on the two major resources for developments of a nation, and in a later stage recognised the need for further removal of economic, technical, cultural and regulatory barriers in order to realise the dream of the European unification.

To conclude that the technological network is purely a political work with a “hidden agenda” is, however, not entirely true when you ask those who have materialised or envisioned these technologies. The engineer-led trans-European electricity network committee UCTPE (UCTE) is a perfect example of a technical successes, given that their purposes were to increase efficiency and stability of energy transfer within Europe. What happened is that, irrelevant to the technologists’ concerns, the electricity network did create a functional spillover effects to other domains in the EU, which is pretty much well-aligned with the Council of Europe’s visions.

Value-embedded technologies: A nation-building agenda of the EU

The creation of the series of technological systems and networks is by and large both pragmatic and accidental. Approaching to the 1990s, Europeans have experienced not only growing internal expansion and economic interdependence, they have witnessed and impacted by the Cold War and its American ally’s actions in Vietnam, which is very much contested amongst the citizens in the member states of the European Community. Moreover, in late 80s and early 90s, the German reunification, the dissolution of the USSR and the break-up of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia altogether casted doubts about the future of Europe and what it means for the “free, peaceful and democratic” Europe that is laid down in the treaties.

Technologies have reunited Europe in a material and economic sense, but also in a normative and metaphysical way. Regulations and projects such as the abolishment of border control under the Schengen Agreement, the Erasmus Programme (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) and EU regulation on roaming all contributed to the elimination of mental and physical boundaries of the nations and the peoples. The European unification programme, nevertheless, has simultaneously amplified the socio-political and cultural differences between citizens of member states or the states themselves, as they all now have more opportunities to encounter one another.

Yes, eurosceptic critiques are commonplace and voiced by most, if not all, European populist politicians. The issue, nonetheless, is much larger than Europe itself. EU now finds itself between the two superpowers – China and the U.S. It is a dilemma for EU. Neither does EU want to be involved in the new Cold War nor EU can survive in the era of globalisation without collaborating with their potential strategic challengers.

We can now see that technologies play a role in EU rather different than before. On one hand, EU and its member states strives to reinforce its digital sovereignty by detaching themselves from their American counterparts and prevent non-European tech companies from entering the market for the sake of security reasons. On the other, culturally, EU is progressively intensifying the notion of the value-driven EU technological landscape through regulations to distinguish themselves from their competitors, as seen from the first quote of this article.

A nation-building agenda of the EU is clear, but the effects remain vague. While EU is working towards a more united political entity that is driven by a set of European values, the danger of an EU nationalism and protectionism is on the rise.

Recent Comments