In 2022 the entire screen of my iPhone fell off; there were no external scratches or bumps, no clear damage to the phone, yet the whole digital screen separated from the rest of the device. After desperately trying to repair and mend my phone for weeks, it was clear that I would not be able to access this device again. As a result, I lost every message, every photo, and every digital memory since 2016.

Over thirty thousand photos, that when combined appeared as a tech scrapbook or a digital montage of my pre-teen and teenage life, were gone. Snapshots of my siblings and parents, of exciting experiences with friends, and of memories that I desired to not only mentally remember but digitally store and hoard for future recollecting and remembrance disappeared. Even after pessimistically viewing new technological media, mediums that either encourage growth or destruction within our society, I admired and loved its dominant implementation of memory through storing tools; these instruments positively granted me the possibility to store digital souvenirs in an accessible manner.

Additionally, as E.F Risko and et. al mention in their article Offloading Memory Leaves Us Vulnerable to Memory Manipulation, published in 2019,

“The recent proliferation and increasing availability of mass storage devices presents our species with a remarkable opportunity to store large amounts of easily accessible information that is immune from the vicissitudes of our biological memory”.1

Nonetheless, while digital memory is no longer subject to alterations, as they can no longer be mentally transformed, forgotten, or altered, these snapshots would eventually be passively forgotten due to the lack of the need to recall and remember. For instance, instead of nudging myself to remember events and stories, I could easily pull out my phone and take a quick snapshot that I would quickly disregard and neglect. Therefore, losing all these fragments of the past, snapshots that became part of a digital museum within my device, forced me to recognize and acknowledge this problematic reliance on digital storage tools that new media has created.

This reliance removed the importance of active and passive remembering, and destroyed the significance of old media and its dominant connection between physicality and memory. Therefore, while the loss of all my photos initially presented as a dwindling of my past self, I quickly discovered and grasped how notable and crucial old media is in the act of remembering, presenting my identity, and eliciting emotions through its physicality.

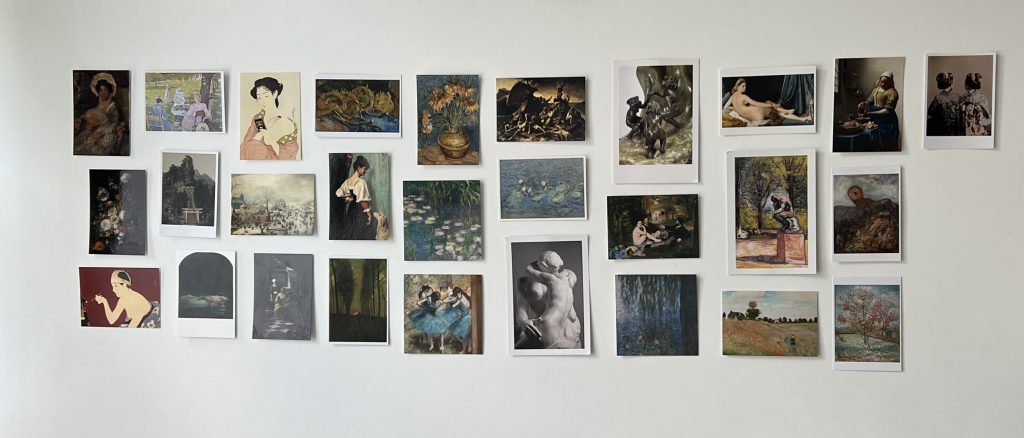

Photograph of some of the postcards from museums that I have visited

Shortly after losing all my photos, I began conceptualising and constructing small microcosms of my interests and experiences. For instance, I started collecting postcards of my favourite artworks from each museum I would visit, physically inserting aesthetics and beauty within my home as a way to brighten my surroundings, visually express my curiosities in art, and plainly reveal my identity. Additionally, I began collecting free pamphlets from museums and art galleries, cutting out hundreds of artworks that I still continue to plaster all over my walls; even currently, a huge stack of art is patiently waiting on my desk for me to pay attention to and hang up. Yet again, the physical quality of these artworks and viewing them help to elicit the experience of seeing them for the first time in person. In turn, transforming these photographs into active objects as “…photo-objects exist in relationship to the human body, making photographs as objects intrinsically active in that they are handled, touched, caressed”.2

As a result of the physicality of old media, I am able to purposefully recall past experiences. This draws out emotions and memories, which help not only in recollection but in nostalgia and the creation of my identity.

In all, through losing all my digital snapshots, I began to appreciate old media and its significant connection between its physicality and memory: how it aids in aesthetically brightening my mood, perceivably communicating my interests and characteristics, and improving my sense of recollection through its activeness.

As I glimpse around my room and notice the abundance of old media, I begin to value and admire its relationship to nostalgia, sentimentality, and remembrance. An association that is more difficult to link with new and digital media.

Thank you! Let me know in the comments your opinions about the relationship between Memory and Old Media – additionally, if you think this relationship greatly differs compared to the connection between Memory and New Digital Media!

Bibliography

Edwards, Elizabeth. “Photographs as Objects of Memory.” In The Object Reader, by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, 331-42. London: Routledge, 2009.

Risko, E. F., M. O. Kelly, P. Patel, and C. Gaspar. “Offloading Memory Leaves Us Vulnerable to Memory Manipulation.” Cognition 191 (OCtober 2019): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.04.023.

- E. F. Risko et al., “Offloading Memory Leaves Us Vulnerable to Memory Manipulation,” Cognition 191 (OCtober 2019): 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.04.023.

↩︎ - Elizabeth Edwards, “Photographs as Objects of Memory,” in The Object Reader, by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins (London: Routledge, 2009), 335.

↩︎

I felt a knot in my stomach when I read the first paragraph! It made me think about how I would feel if suddenly my 48,000 pictures would “disappear” and I got this instant desire to print all of my pictures even though it is impossible. It is so because, with the accessibility of carrying a little lens everywhere, we now tend to document everything which then leads to an accumulation of pictures that are either doubled, triple, or blurry. It’s like as if we have become hoarders of intangible memories…

I recently got a notification on my phone, that said that I need to update my iCloud, otherwise, if the iPhone is damaged, I will lose all the data. I immediately got scared and mostly, as I realise now after reading your blog, terrified of losing my photos. Even though, I most likely will never look at some random photo of some building I took 4 years ago, the idea of having it somewhere on my phone comforts me… This shows that the “problematic reliance on digital storage” as you accurately formulated in the text is, in fact, more influential than we think