History on the internet often takes the form of just another plotline, some facts and events that we scroll through, enjoy, and quickly forget. Something completely different happens when you discover your personal history, even more so when you meet people with whom you share this personal space. This kind of history can consume you completely and keep you up late at night as you tirelessly investigate every lead until you find answers. To get there, you must build the largest online family tree you can, take a few DNA tests, and wait. Sooner or later, your history will find you. In my research, I expanded my maternal tree to include cousins and neighbours. Over the years, this structure has expanded to include diaries, documents, stories, and photos, and is still growing.

I grew up very close to my grandparents and remember moments of wonder as I realized how differently they had been raised. I recall the moment when my elderly aunt laughed off the idea of marriage based on love instead of economic and practical reasons. Or the times when my grandpa had tears in his eyes while talking about being randomly caught by the police for no reason, and how his German-speaking grandpa struggled to take him back home. Or the scene when my grandma, as a young girl, hid in the middle of the night in the currant bushes with her baby brother, out of fear of gangs prowling the area.

I grew up in what seemed like a monoethnic Poland, but only later in life did I discover the rich ethnic diversity that once defined the region: Poles, Jews, Ruthenians, Russians, Germans, and Dutch, all coexisted there. Driven by curiosity, I began analyzing parish vital records to verify family stories. Needing help to translate documents from the Russian occupation period, I joined an online community of local genealogists, and began indexing vital records of villages in the vicinity.

Once, a DNA match uncovered that many of my relatives lived on the other side of the Bug River, in a village marked with the tragic history of the Volhynian massacre. This was a piece of history deliberately passed over in silence for political reasons. I interviewed locals to learn more, and they shared many stories passed down in their families. The local identity has formed across centuries in similar way, by spoken memories. Someone told me that the local parish priest owns a 400-year-old handwritten chronicle that no national archive knows about, and I learned that we are indeed native to the Bug Valley.

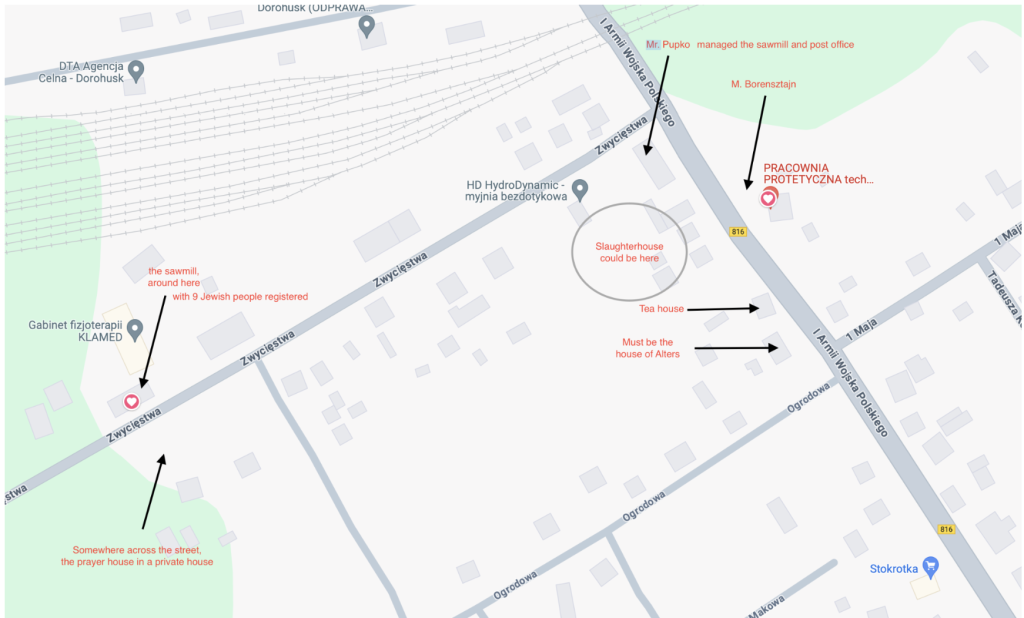

Another time, I was asked by Einat, my DNA match, about her Jewish ancestors named Alter. She shared with me her mom’s childhood memories and a list of forty relatives perished in the Holocaust. We exchanged stories about the fates of our ancestors, how lively and varied their lives were, and how they eventually ended. I began my field research. Although no one remembered Jews in the area, the local library has some publications tucked away on the lower shelves, the regional museum eagerly connects historians, and another aunt of mine lives next to an old grain mill with a pre-war history of unpaid debts and insurance fraud involving Jewish entrepreneurs. Soon, I found Einat’s family house, the location of a slaughterhouse and a tea house they once owned, and prenuptial papers with home inventories. In the end, I found people who remembered the names of the family. I drew a map and shared it by email. The anecdote I heard from older people was that after Tovia Alter came back from deportation to Siberia, he returned to the village to sell his family property, authorized as the only survivor. He joked with Mrs. Słomska, a trader like him, whom he knew and liked: “Mrs. Słomska, let your daughter come with me, she’s so good at keeping the store. I’ll take her to Israel, she’ll have a good life.”

Einat received my email while in Germany, having been forced to flee because her home in Israel is now under constant bombardment, and she had to escape with her little grandson, seeking safety. Despite the upheaval, she tries to stay strong, keeping her head high and remaining brave in the face of such adversity.

When she opened my message and saw the map I had drawn, showing her ancestors’ homes and the places they lived, she was deeply moved. “It felt to me like a postcard with greetings from the past,” she told me, as if the echoes of her family’s history were reaching out to her across time and space, lending a sense of connection and continuity in the midst of her present uncertainty.

In my research, the online and offline worlds work together. Visiting museums, talking to elders, and exploring places gives me important information, but it’s the internet that helps bring everything together. The online connections, access to records, and reaching descendants across the world allow me to return these stories to their rightful place. Without the online, much of this wouldn’t be possible, and so many stories would remain forgotten, with no one left to remember them.

Super interesting blog about your family lineage—thanks for sharing! I found it especially fascinating how the digital world often seems to serve as an entry point for genealogy research. Taking that next step into the offline world, however, can feel quite intimidating. It’s not just about the added time, effort, and money (which can be a barrier for many), but also the courage to step out of your comfort zone and connect with strangers.

Digitizing more resources, like the handwritten chronicle you mentioned, could certainly make this type of information accessible to a much wider audience. At the same time, I wonder if it might diminish the unique “experience of the journey,” where the effort itself adds to the personal significance of the discoveries.

Do you think the benefits of wider accessibility outweigh the potential loss of that journey, or is there value in keeping some information offline, reserved for those willing to dig deep?