When one speaks of observable digital inequalities in their personal lives, it’s usually about how older generations are incapable of using technology and do not have the same level of digital literacy as the younger generations. Whilst the current youth culture is practically defined by smartphones and social media, it takes a few frustrating personal experiences in the absence of digital access to realise what it means to be digitally marginalised.

Taking the term the ‘digital divide’ to mean the lack of access to information and communication technologies, but more specifically focusing on the inequalities in terms of physical access, the following addresses some of my rather mundane experiences of digital inequalities which prompted me to delve deeper into the greater implications of the digital divide on society as a whole (Van Deursen and Van Dijk 2021).

NHS Track and Trace (UK)

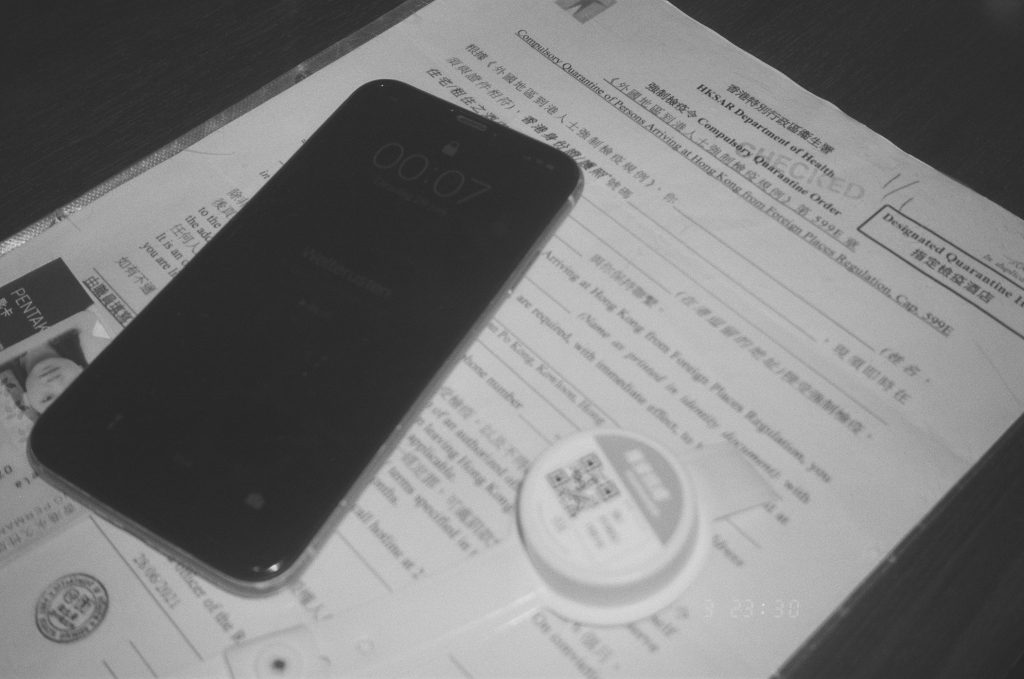

Equivalent to the CoronaMelder app in the Netherlands, this was a mobile application launched in September 2020 as part of the UK’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst initially met with a lot of scepticism, for any socially-deprived young person who wanted to visit cafes, pubs, and restaurants again, it became almost mandatory for you to have this application on your phone.

However, even when you successfully manage to ignore its functional (in)capabilities as well as the associated privacy and surveillance concerns, it didn’t take much for any individual to become digitally marginalised from what was supposedly an openly accessible mHealth tool. From the onset, those without smartphones were immediately eliminated as potential users. And for those who owned smartphones, either you had an Apple device with iOS versions 13.5 or higher or an Android device with 6.0 (Marshmallow) or higher, or you did not qualify to be a user of the application (NHS 2021).

As a then user of a second-hand iPhone 6S, my phone was fortunately able to carry the application but this was short-lived. The reopening of the country in Spring 2021 meant a return to the ‘new normal’ which demanded that I rebuild my relationship with my phone (which I had set aside during the pandemic as part of an attempt at reducing screen time) and find a way of working with a device with visible physical impairments, no available internal storage and a battery life of less than 30 minutes.

It occurred to me then that I was going to become a member of the digitally-marginalised if I didn’t switch out my phone. Whilst my phone was lucky to survive the IOS updates of the previous year, the device was already 6 generations behind the newest model and was being targeted on online tech forums as the next iPhone to face elimination. In combination with changes in my daily routine in terms of going back to university and work, which relied largely on real-time communication via smartphone, it was impossible not to make the switch.

Tikkie, IDEAL and DigiD (NL)

Reflecting on a much more recent experience, my period of transition to the Netherlands over the past month has also inspired me to read more into the digital divide in the Dutch context. Starting with a personal anecdote and moving on to engaging with some broader areas of research, the following section aims to draw connections between my observations and the wider social context.

Like any other incoming exchange student with time on their hands, I thought it was a good idea to do some research in preparation for life in the Netherlands. Namely, I started by downloading some of the most widely-used mobile applications in the country. From DigiD to Buienradar, I thought I was digitally equipped until I discovered that I couldn’t find Tikkie on my app store.

I tried directly searching for it online. I tried using a VPN to access the Dutch app store but I still couldn’t find it anywhere. Whilst it was later revealed that it was a matter of changing the payment method on the app store, I was shocked to discover stark similarities between my experiences with Tikkie and PayMe; daughter application under HSBC and widely used in Hong Kong as a social payment method (Come and Stay 2021). In both cases, I was unable to locate the applications on my app store and was therefore unable to access some of the most basic services such as online payment.

Similarly, in the cases of DigiD and iDEAL, the prevalence of these two digital tools when it comes to communication with the government, access to public services, or performing online payments was incredibly eye-opening for me. Whether as mobile applications or as traditional web pages, the importance of Internet access and digital literacy is non-negligible. As emphasised by Derek van den Nieuwenhuijzen and his research on low literate people and digital skills, ‘the digitalisation of Dutch government forms is putting pressure on low literates, digital illiterates and non-native Dutch speakers’ (Bon et al 2020, 50).

Whilst my personal stories of unequal access touch only on very basic themes of digital inequalities, there are many other kinds experienced within the context of the digital divide. However, when extrapolated onto a larger scale and applied to different social and cultural contexts, it’s important to recognise the relationship between unequal access to digital technology and unequal participation in society (Van Dijk 2017, 3). Against the backdrop of a neoliberal political and economic context, the role of the digital in the reinforcement and perpetuation of social inequalities is a topic I would like to unpack further in future posts.

References:

Van Dijk, J. 2017. Digital Divide: Impact of Access. DOI:10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0043. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314732108_Digital_Divide_Impact_of_Access

Bon, A. et al. 2020. Digital Divide, Citizenship and Inclusion in Amsterdam. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339124074_Digital_Divide_Citizenship_and_Inclusion_in_Amsterdam

Online Resources:

Come and Stay. 2021. “Change to Dutch app store without a credit card”. https://comeandstay.nl/faq-items/change-to-dutch-app-store/ (Accessed 19 September 2021)

NHS. 2021. “Which phones will the NHS COVID-19 app not work on?”. https://faq.covid19.nhs.uk/article/KA-01116/en-us. (Accessed 19 September 2021)

Van Deursen, A. Van Dijk, J. 2021. “The Digital Divide – An Introduction”. Centre For Digital Inclusion. The University of Twente. https://www.utwente.nl/en/centrefordigitalinclusion/Blog/02-Digitale_Kloof/ (Accessed 19 September 2021)

Recent Comments