Not so very long ago most computer users printed everything. They held onto their paper texts, probably also because the average pre-millennium (Windows) computer was quite unreliable and crashes happened frequently. Files were much easier damaged than nowadays. Making backups was easily forgotten, so a printed hardcopy was something to rely on. The ‘paperless office’ existed in theory, but not in practice.

Only slowly this way of working changed. Imagine we still printed every document, would’t that cost an awful lot of time and paper? The portable laptop lessened the need for printing and the e-reader and tablet made us even more mobile. And let’s not forget the most mobile device of it all: our smartphone. We can consult our documents everywhere we go, but we shouldn’t forget to make backups on a regular basis, in the cloud or onto an external data carrier.

But who is responsible for making a backup of our collective data, the information the government keeps about us and our cultural heritage? Everything we don’t want to consult immediately but maybe later and that is worth conserving. Maybe not by ourselves, but certainly by the generations that will come after us. The archives take care of this. Imagining an archive we usually see researchers in quiet reading rooms bent over parchment charters with wax seals attached and elderly people investigating their family trees. But ‘documents’ are increasingly ‘digital born’, which means they only exist in digital format and the archives are certainly not going to print them all and put them into boxes.

Information in archives is meant to be perserved ‘for eternity’, which means as long as possible. And that’s not always an easy task. Printed material from between 1870 and 1945 is often liable to deterioration because of the cellulose paper. Digital scanning or mass deacidification treatment prevent the information from getting lost forever.

In the Netherlands it is stated in the Archive Law (Archiefwet) that government documents should be stored in public archives and can be consulted free of charge after twenty years. This means the information must not only be stored, but should also be accessible. It will have to be organized in a way so researchers can find answers to their questions.

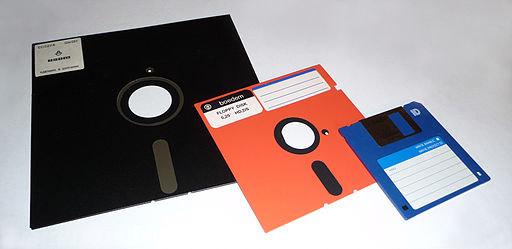

How long will digital information be consultable? We are facing different problems here. First of all we should differentiate between hardware and software. Computers age rapidly. When someone offers information stored on a pre-millennium ‘floppy disk’, the data can only be read by a ‘floppy disk drive’. Once we read the data, we should have access to the software that will deal with it properly. If that’s not the case and the data can not be converted into another format, the floppy disks will be of no use.

Apart from that it will be possible that the information on the floppy disk is corrupted because of damage by heat or water. The creators of the so called M-DISC (Millennial Disc) claim that their discs will last a 1000 years or more. Their story sounds convincing but we will never know if they will live up to their promises.

References

Dutch laws and regulations concerning government archives: https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/archiveren/kennisbank/wet-en-regelgeving

Netwerk Digitaal Erfgoed (Dutch): https://www.netwerkdigitaalerfgoed.nl/

Information about the M-DISC on the company’s website: http://www.mdisc.com/

The Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal Library) at The Hague about: webarchivering: https://www.kb.nl/organisatie/onderzoek-expertise/e-depot-duurzame-opslag/webarchivering

A handy sheet on ‘preferred data formats’ on the DANS (Data Archiving and Network Services) website: https://dans.knaw.nl/nl/deponeren/toelichting-data-deponeren/voor-het-deponeren/bestandsformaten

The UNESCO ‘Memory of the World’ program: https://en.unesco.org/programme/mow

The photo of the floppy disks was taken by George Chernilevsky [Public domain]. From Wikimedia Commons.

Recent Comments