During the last decades, and especially the last couple of years, debates about the restitution of cultural heritage have gained more and more public interest, forcing western museums to reconsider their role within today’s society and to actively face their legacies of colonialism, slavery, and racism, often failing at their ostensible attempt in doing so.

But precisely what do we mean when we talk about cultural restitution?

“Cultural restitution is the process by which a moveable object of historic or cultural significance is returned to its country of origin. It can be a sensitive and complicated topic.”

– returningheritage.org

When talking about this topic we often also come across the term repatriation. While both, restitution and repatriation generally refer to a transfer of cultural objects, restitution is used in relation to that of stolen objects back to their original owners, whereas repatriation implies that of objects tied to a specific cultural patrimony or place.

What I would like to talk about in this post is the transfer of stolen, or looted, cultural heritage. The looting of cultural artifacts has been happening ever since artifacts themselves existed and can take on many forms, all of which can be broadly described as unrightfully taking objects. In connection with colonialism and racism, this commonly included acts of unspeakable violence with the intention of eradicating non-Western cultures.

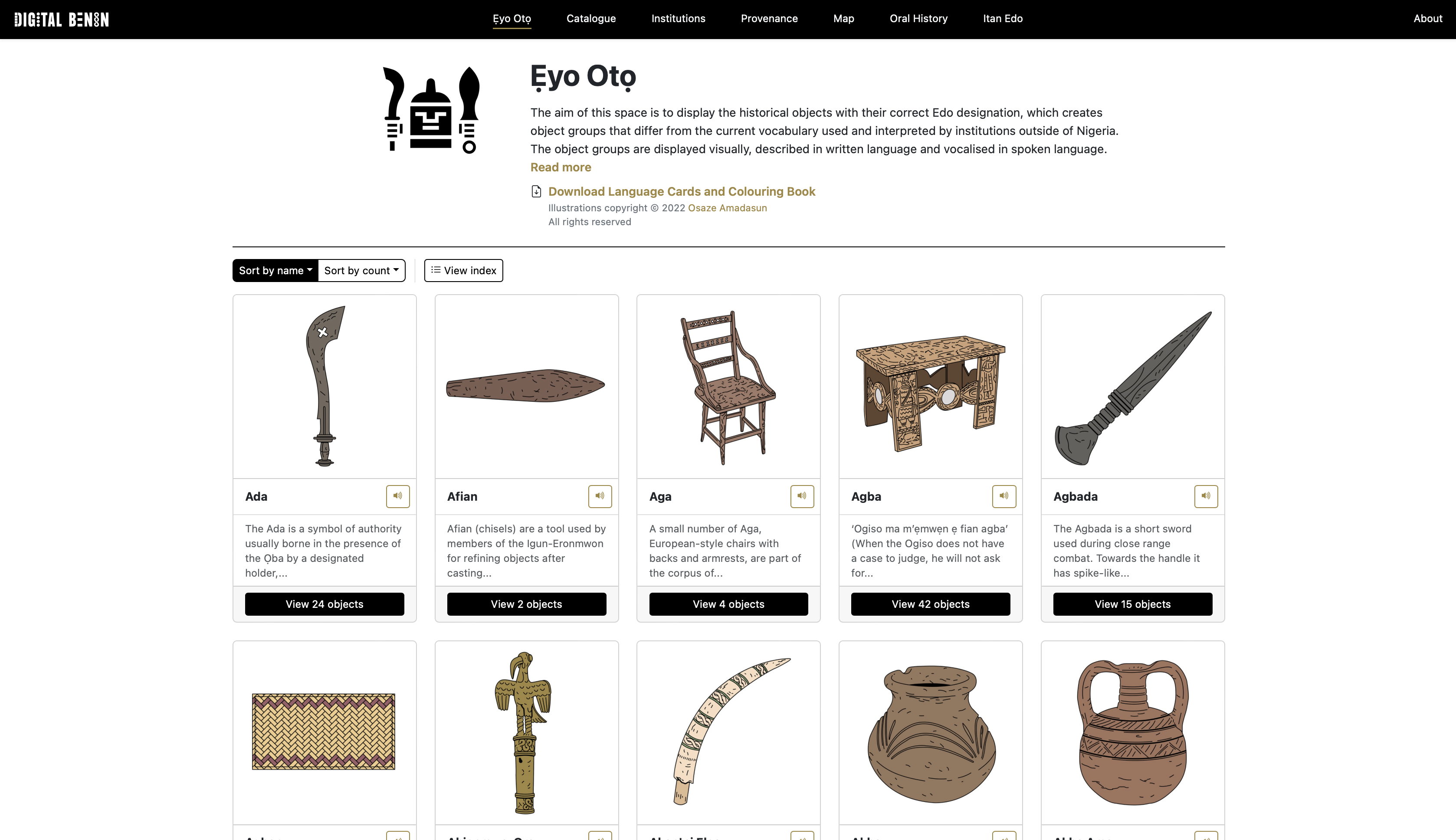

More recent discussions about restitution were sparked in connection with the debates about the Benin Bronzes. The Benin Bronzes are a group of several thousands of sculptures made of brass and bronze, including elaborately decorated commemorative heads, figures of animals and humans, personal ornaments, and many more. They were crafted from no later than the 16th century onwards in the Kingdom of Benin, a major city-state located in present-day Edo State in Nigeria, and embody an expression of its culture, history, and arts. They originally served as royal representational art and were used for the depiction of historical events, communication, worship, and rituals.

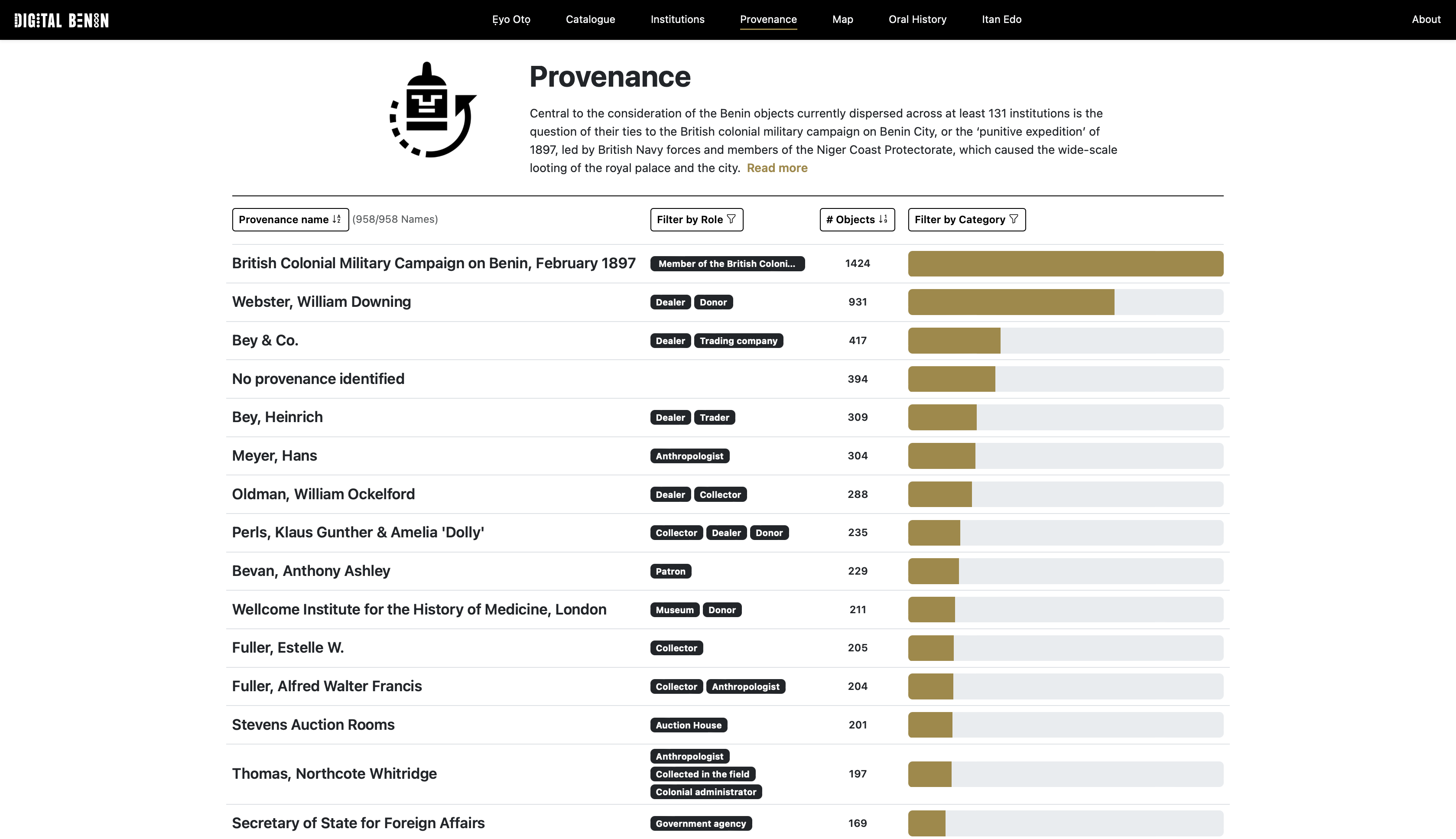

During the Benin Expedition in 1897 British colonial forces invaded Benin City under the pretense of a peaceful diplomatic delegation, destroyed it, and looted these artifacts, almost all of which are still held by more than a hundred different institutions in the Global North, most notably in the British Museum in London (944) and the Humboldt Forum in Berlin (518).

While there are many things to say about the history of the Kingdom of Benin and its Bronzes, I only intended to give a brief overview of the topic, as a proper dive into it would go beyond the scope of this blog post and my own knowledge and comfort zone. The way history is being told tends to be very one-sided, and this certainly counts for that of the Kingdom of Benin as well. For this reason, I believe that it is important to include those affected by these events in the discussions and research in order to allow for truthful documentation thereof. I would therefore like to tell you about a new attempt to do specifically that: Digital Benin.

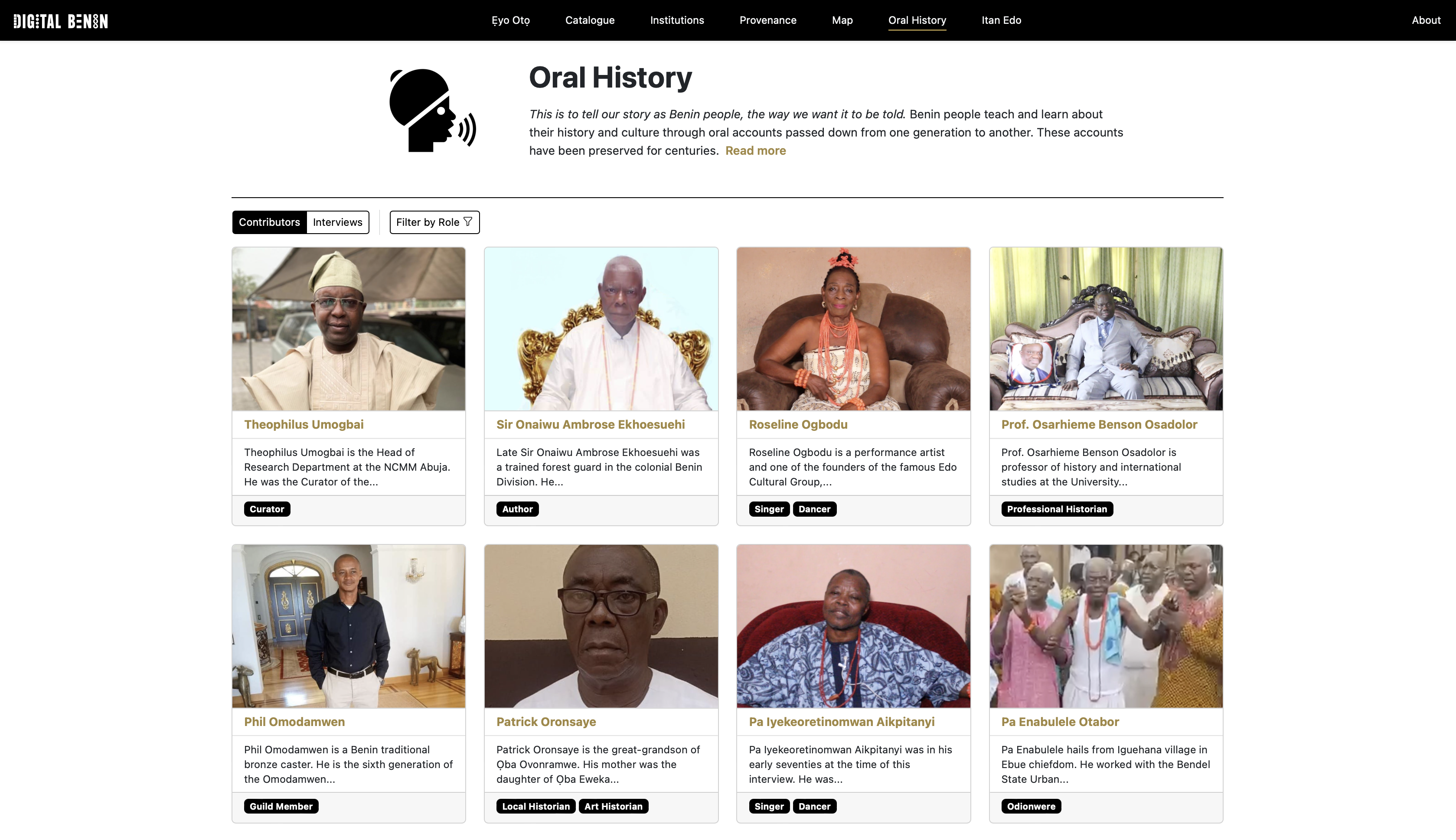

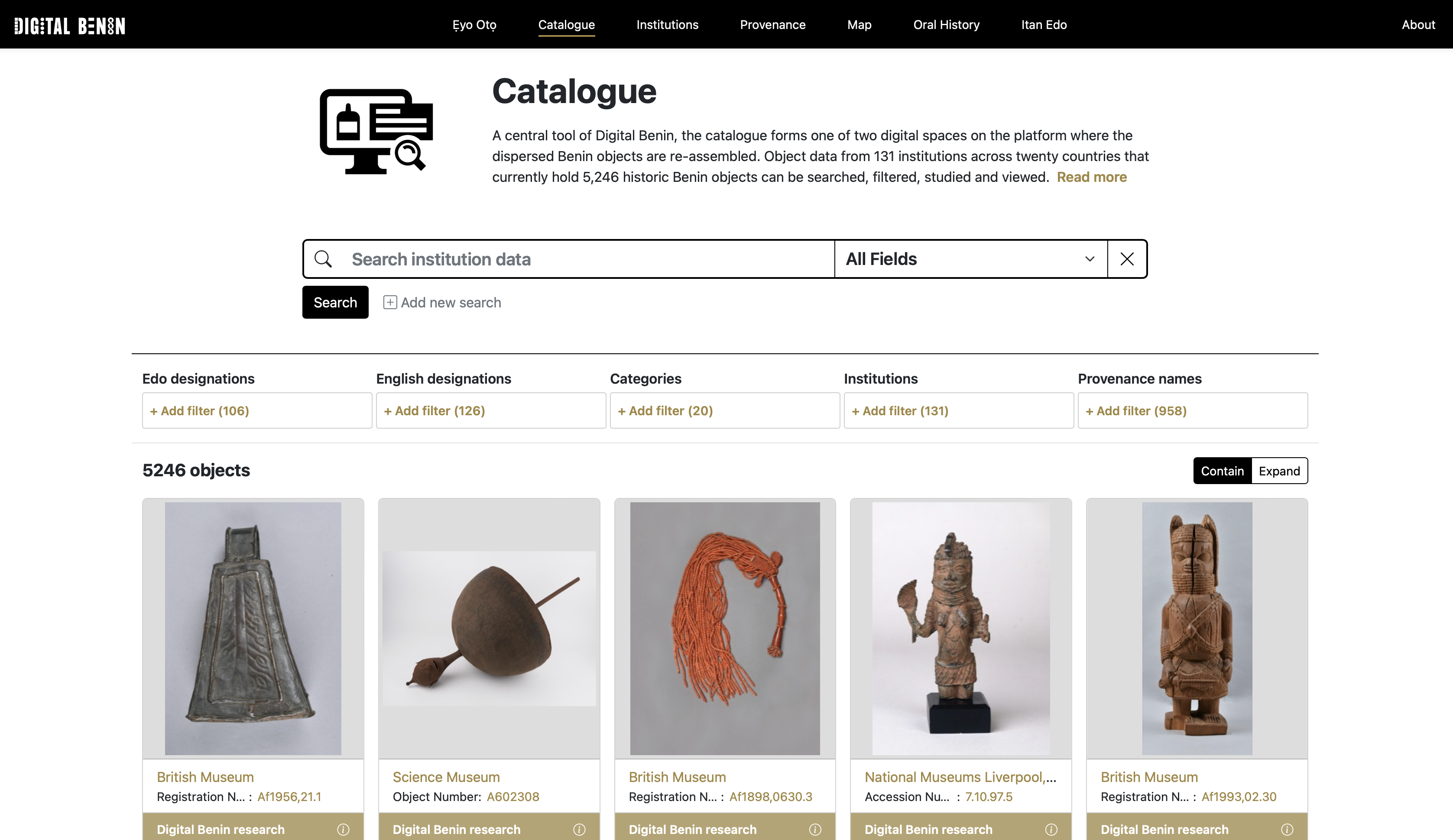

Digital Benin is a digital platform created as the result of a collaboration between 131 institutions from 20 countries that brings together the entirety of objects, historical photographs and documentation material from collections around the globe with the aim of providing an overview of the looted objects from the Benin Kingdom. This novel scholarship links digital documentation of these objects to ‘oral histories, objects research, historical context, a foundational Edo language catalogue, provenance names, a map of the Benin Kingdom and museum collections worldwide,’ adding up to data from 5.246 objects across the institutions.

While this approach cannot be a replacement for the ongoing process and debates of restitution, I feel like it does offer a great way for people to learn about the historical and cultural heritage while illustrating the gravity of these events and the colonial legacies of countries and institutions from the Global North. To conclude, I would like to add these two quotes from the research lead of the project in Benin City, as I believe that they perfectly outline the ambition of this project.

“What we are launching is a platform that will enable the young generation of Benin/Ẹdo people to learn about the rich historical and cultural heritage of Benin with a sense of national consciousness that speaks to the essence of the civilisation from our past that is present in our daily ceremonies and rituals”

Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie, research lead on the project in Benin City

“The platform has and will preserve for future generations the significance of our cherished cultural values and practices as an educational tool with materials like oral traditions, which will help Ẹdo people learn about their ancestors as if the contributors are speaking to them in a real life situation.”

Osaisonor Godfrey Ekhator-Obogie, research lead on the project in Benin City

Sources/References

Digital Benin

“About Cultural Restitution,” Returning Heritage.

“Benin Bronzes: Temporary Redesign of the Benin Rooms,” Humboldt Forum.

“Contested Objects from the Collection: Benin Bronzes,” British Museum.

Simon Stephens, “Digital Benin project unveils online platform,” Museums Association, 15 November 2022.

Hey! I really liked your post, I didn’t know about the existence of Digital Benin. I think it’s a really amazing initiative, especially given the fact that much of the debate around restitution and repatriation is heavily based on ignorance regarding the cultures of origin. Creating a space for education regarding looted objects can be a great way to teach people about the cultural and artistic heritage of non-western civilizations and about the history of colonialism and the looting of objects as war trophies.

This is a really cool project that you have brought up, and I really liked your presentation of it. I completely agree with the fact while this initiative can certainly not replace the return of the objects, our contemporary digital age offers valuable alternatives. The fact that museums hold these object today represents a troubling colonial history that has to be confronted. Nevertheless, this project can do nothing but good, and hopeful partially aid in undoing the lasting damage that their absence has caused, through education and open discussion.

I have looked very closely at this project as you may now from our conversations 🙂

I still worry for the “big 5”, european museums, seeing this as a form of restitution in combination with maybe loans. It would beat the purpose I think.

I also very much question the accesibility of ‘users’, and if they differ from current museum visitors (aka, questioning if its still mainly for the western gaze).

I do see it as a framework, since they combine oral history and inatitutional knowledge to establish provenance and distribute knowledge. But again access… I wonder how many people know about this website and what the day-to-day use could look like.

Cool project! It is a good example of making heritage more accessible with a website. In the case of digital Benin I hope that it creates more awareness of its cultural and historical heritage. The website looks good and is informative.

It is a cool project in deed. However, I am also concerned that whether this will service as the reason for not giving back those Real objects at least for now. It’s pros and cons are the two sides of the same coin– the possibilities of “duplication” because of technology. In this case, the discussion of where the real objects should belong to becomes even more difficult for the side of Benin, since one of the reasons to return immediately was weakened. Even though the original intention for digitalization might be good, its result could be used by politicians or other people serving their own purposes.