The question of if online creators should get paid for what they do is a controversial one, but one thing is certain: there is an enormous business booming around the world of advertising and sponsorship, which makes the internet a breeding ground for young (sometimes undeserving) millionaires.

It is relatively easy to come across displays of immense wealth on social media (specifically, Youtube and Instagram), where as young as teenagers are suddenly paying their own rent and living extravagant lifestyles, but this begs the question: how did we get here? Is this ok? Or are we glorifying consumerism and selling our attention span to the free market?

On the one hand, paying online creators emerged in order to retribute those who were a) earning their living on the internet with a business and b) those who were creating content of artistic value on their online platform. Often, this happens at the same time.

I think we can all agree that musicians and artists deserve to be retributed for what they do. But while I think that, I also squirm at the idea of giving Spotify €9,99 a month. My issue is that when relating to art, an element of it is definitely lost if there is an intermediary such as a corporation. As easy as it is to sympathise with a street artist, so it is difficult to do so with an artist with sponsorships, advertisements and millions of dollars.

So the paradox: on the one hand, corporations know that involvement with online content leads to their brand getting closer to its consumers, on the other this process wilts the authenticity of the art itself and makes the artist a business rather than an artefact.

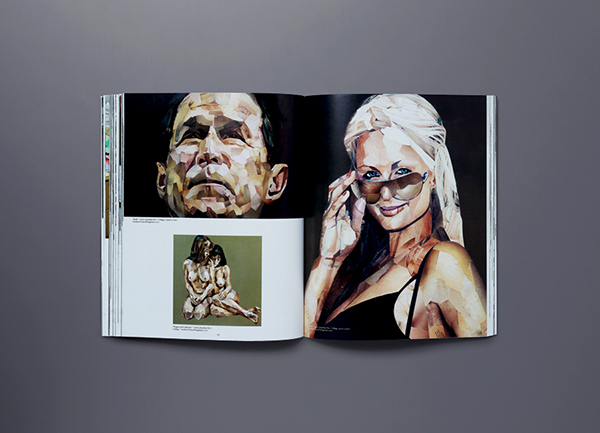

But the process does not stop here: seeing as corporations base their investment on engagement with internet users, larger funds are going to creators who summon more engagement, not more valuable content. This means that this

is getting the more economic return than this

Quite apart from its artistic value or my personal preference, it is abundantly clear which of the videos required more effort, more planning, more expertise and more funds to produce. Yet the first performer, Trisha Paytas, makes about $2000 a day according to multiple online sources.

In worse cases, many Youtubers earn their popularity simply by displaying their own wealth and lifestyle. This leads me to think that many online communities are no longer populated by unknown artists waiting to be discovered, but by reality stars waiting to be cast in their own reality shows, owned by companies that hope to use creators as a showcase for their products.

We may not agree with paying reality stars, but it certainly beats paying a 31-year-old woman to sit at home in her kitchen singing badly on purpose, only for the purpose of outraging (but also engaging) her audience.

The internet is no longer a community, it is a business platform, or at best a showroom. We must accept this shift and treat it as such. As many business platforms, it listens only to the demand of the market and not to artistic value.

There is quite some truth to be read here…

Nowadays YouTube especially feels like a big hype machine.

Everyone tries to game the algorithm and capture our attention with outrageous thumbnails and the like..

I remember when I tried to explain my parents to concept of Twitch.tv with Ninja as an example:D

They couldn’t wrap their had around how this guy earns millions and millions by merely playing a video game..

On one hand I agree with you, on the other hand it also depends on which platforms you look at, and which subcultures. In many ways I believe there are many people trying to profit from these platforms, yet there are also still large groups of people who simply join to find a community and for fun

I still think that the sense of community on the Internet is very strong and a priority for many users. But I also agree with you when you said that entertainment has become a priority for most people. I think that, in the short-term, being outrageous had always been more profitable than quality content or products in any field, media or environment. Maybe nowadays this is more evident since as a society we value anything that is short-term over the long-term? (I hope this makes sense…) Is instant gratification/attention (which comes easily with outrageous behaviours rather than quality content and products) more sought after than ever? I think it may be a pattern that we see in non-digital fields too, like fast fashion. And, to be completely honest, I as I write this I am also questioning my own words so feel free to go against what I just said ahah